2025's Summer of Horror

As we near the halfway reading point for 2025, this year’s horror fare has already started to eclipse 2024. As a reader and reviewer, I had focused on recently published books last year in an effort to pick up on trends. This isn’t always recommended, since you often end up selecting presently popular books rather than ones you’re actually likely to enjoy. So for 2025, I added in a number of horror classics and recommendations from years past.

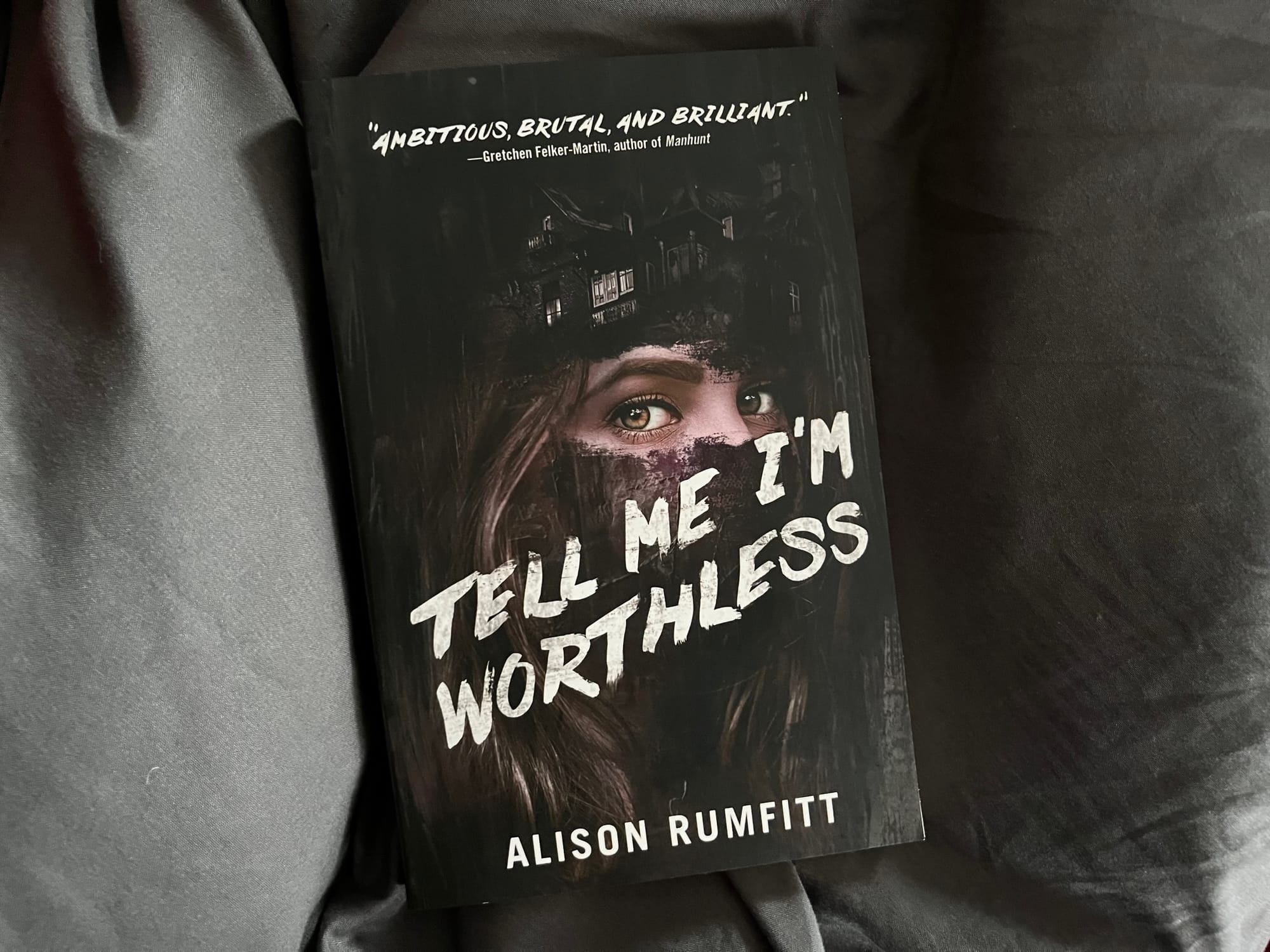

This included diving into a few authors I had always intended to read but hadn’t, especially Alison Rumfitt. Rumfitt is among the most discussed and shocking voices in a slew of trans body horror that has hit American bookshelves over the past several years. She uses the frightening nature of bodily transformation — or the failure of a body to shift and conform in the direction its owner requires — as a jumping-off point to examine the nightmarish attack on trans lives in a rapidly devolving British political world. It’s hard not to think about the now recent April 16th U.K. Supreme Court ruling in For Women Scotland Ltd v. The Scottish Ministers, which determined that the 2010 Equality Act refers only to biological sex. This ruling expressly targets trans women, excluding them from women’s single-sex spaces such as bathrooms. It came just a couple of months before a similar U.S. Supreme Court decision, United States v. Skrmetti, where a 6–3 decision upheld Tennessee’s recent ban on hormone blockers and therapy as part of a youth gender medicine program. That ruling immediately triggered laws in 20 states to become codified, ensuring one of the most brutal attacks on trans healthcare in American history. Meanwhile, the President recently prohibited trans people from military service, claiming they were neither healthy nor morally upright.

Rumfitt’s work intentionally blurs the lines between the personal and the political, between her characters’ bodies and the world they are operating in. I started with Tell Me I'm Worthless, a frenetic character story that looks at how Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminist (TERF) politics interweave with a culture of abuse and trauma, and how the underlying logic of fascism is a state of reactionary violence and identity that has traced through British history. It does this by centering the characters in a mutated haunted house story, where the events of violent persecution the building once held become the origin point for shifting our characters to victimize each other. The book is brutal and challenging, but its analysis of fascism finds its origins in the work of people like Gilles Deleuze (1925–1995) and Félix Guattari, and examines how “microfascisms” sit underneath even the most daily occurrences of cruelty.

The book is well-plotted, though it only relies on horror conventions lightly — a perfect mix of literary and genre writing, plot, and escalating fever dream. Her next novel, Brainworms, which I turned to next, was even more firmly set in a horror storytelling model, though it never fully settles into its narrative long enough to feel perfectly familiar to the average horror fan. Instead, we hear a multiple-character story about the violence of transphobia, envisioned as a parasite sitting in our brains and passed between people through sex, violence, or both. The book is harsh and upsetting, particularly in its grotesque intermix of fetish and parasitical obsession, and in that way feels most familiar to the work of Eric LaRocca. And while it’s incredibly successful in using the conventions of body horror to parse out a metaphor for the shifting bigotries and institutional terror of British society, it missed a number of opportunities to draw out the plot more clearly in ways that would have made the ideas simply more coherent. Nonetheless, by the end of the novel the reader is taken on such a destructive journey that it’s hard not to feel the punch in the gut that dissolves the characters’ sense of themselves. Rumfitt is an author like Hailey Piper, Poppy Z. Brite, or Gretchen Felker-Martin, redefined queer horror by using well-worn horror devices and deconstructing them just enough to be familiar while pushing readers into experimental prose and waking nightmares.

Subscribe to the newsletter

With a lot of travel over the last few months, I focused back on well-recommended horror favorites, starting with Nick Cutter’s The Troop. While not as enticing as his 2024 novel Queen, it follows a similar line of body horror, watching as a Boy Scout troop declines on a remote Canadian island after encountering a painfully sick — and ravenously hungry — stranger. The book has a Lord of the Flies retread, which works to a degree, but it slows down about two-thirds of the way through as it focuses on wilderness survivalism and introduces a late-entry villain who feels both overexposed and underdeveloped. But the pacing picks back up, and Cutter’s balanced prose respects the reader without unnecessary tangents or unearned sentimentalism.

The same might be said for Sarah Gran’s Come Closer, except at a tight 150 pages, it may be an example of a perfect horror novel. A couple notices some weird tapping somewhere in their apartment that’s hard to locate. Then they begin to fight, though they hadn’t before. And why can’t our narrator remember every part of her day? There’s not a wasted page in this book as it takes us through a shockingly engrossing horror story — one that hits every genre convention not by redefining it, but by inhabiting it with expert craft and reverence for the type of fear well-trodden fables can inspire. While I’ll avoid spoilers, it was also a surprise Jewish horror novel halfway through — something that’s both rare and seems largely undiscussed in analyses of the text. It’s a favorite in the HorrorTok world and, though nearly 25 years old, it remains a top entry on almost every “scariest book ever written” list. It may not be a classic among the literati, but it’s one of the best examples of a horror family favorite.

Part of my backward look into horror classics has included diving into short fiction, and Ellen Datlow’s Darkness is a great place to start. The book collects some of her favorites, beginning in the 1980s with Clive Barker’s The Books of Blood and continuing into the early 2000s. This was a high-water mark for many of the horror authors we now know as defining voices in the field, so we see mostly established faces in its pages: Stephen King, George R.R. Martin, Joyce Carol Oates, and so on.

What’s especially interesting is the way the book formulates the boundaries of the genre. Many of the stories carry nothing supernatural — or even out of the ordinary — and instead the horror often emerges from disturbingly relatable pieces of literary fiction. For example, both Oates’s and Staub’s entries are largely about sexual abuse, without anything even hinting at a genre convention. Abuse is often a central theme of modern horror fiction because the abstractions of monsters or hauntings act as proxies by which to process the lived terrors experienced at the hands of very human creatures. But that is clearly not the logic this collection operates on, and it reminds the reader a bit of an older conception of what horror was — before it was even a distinct genre (which, as a commercial category, didn’t really come into its own until the 1960s, after the release of Rosemary’s Baby, and primarily as a marketing device).

If you read collections of older, pre-Poe horror stories, they’re often gothic tales or narratives about people encountering others not like themselves, where the horror emerges from discomfort, strangeness, or fear itself. I’ll note that both of those stories were brilliant, as are a number of others in the book. There are particularly fabulous entries like “Calcutta, Lord of Nerves” by Poppy Z. Brite, “The Dog Park” by Dennis Etchison, “The Greater Festival of Masks” by Thomas Ligotti, “Two Minutes Forty-Five Seconds” by Dan Simmons, “Rain Falls” by Michael Marshall Smith, “The Tree is My Hat” by Gene Wolfe, “No Strings” by Ramsey Campbell, and “Stitch” by Terry Dowling.

One particular entry also stands out as one of the rare examples of a classic Jewish horror story: “Dancing Man” by Glen Hirshberg. This story is also collected in Ellen Datlow’s celebratory anthology Edited (which I recommend for Datlow’s favorites from horror, fantasy, and science fiction). It’s one of the few post-Holocaust Jewish stories that offers a productive, thoughtful reading of Jewish trauma and the ways in which it’s been passed down as a difficult, sometimes unspoken adjunct to Jewish identity and tradition. It absolutely belongs on any list of Jewish genre fiction.

Subscribe to the newsletter

One book that I had sadly ignored since its 2023 release is Gabino Iglesias’ The Devil Takes You Home, which has been hailed as a near-instant classic. The book is an expert study of grief, landing blow after blow on the reader from the opening pages. It ultimately creates a brilliant allegory and supernatural paradigm for the descent into crime and, eventually, a kind of transcendent evil as we watch our main character’s delusions over repair and redemption drive him deeper into the world of cartel violence.

This could be a near-perfect novel, but some rather pedestrian attempts at political commentary hold it back in moments that really needed the kind of muralesque subtlety the rest of the text provides. For example, as a years-long cartel member leads two others toward their ultimate rendezvous with violence, he stops to have a fight with a group of white, blue-collar workers and lectures them on structural white supremacy. The politics of these discourses are largely fine, but they’re delivered with such a blunt edge and feel so out of step with the narrative and dialogue of the characters that it seems as though the author was unable to fully realize the political ideas clearly floating above the material.

I’m reading this at a time when ICE is invading many of the cities mentioned in the book with paramilitaries, tearing families apart and terrorizing entire neighborhoods, and so the inability of the text to render these observations in a way legible to the story at hand felt jarring enough to momentarily pull the reader out of the world it had built. That said, the horror elements and the crushing grief at the heart of the storytelling were so strong that those brief, clunky moments were easily forgiven.

Part of my look at classics brought me to Valancourt Books, which has been republishing a lot of out-of-print horror favorites, particularly as part of Grady Hendrix’ Paperbacks from Hell series. But what is perhaps even more interesting is their new international horror series, which has both some collected anthologies of favorite selections and has focused on a few particular authors, mostly in the world of esoteric cosmic horror. Two new collections, Swedish Cults by Anders Fager, a Swedish horror writer, and The Black Maybe, written by Hungarian Lovecraftian author Attila Veres. Given that the world of Cthulhu Mythos writing in the U.S. is hopelessly stagnant, it is shocking that these authors, who work directly in Lovecraft’s mythos, and yet do so in such a stunningly original and engrossing (and modern) way shows just how powerful the language barrier can be. Both authors focus on the cultish elements of the mythos, and Veres in particular takes seriously the idea of a Cthulhu-cult operating in 21st Century Europe. For Fager, there is a baroque subtlety to how the themes emerge, with dread-inducing longer short-stories that draw out only the briefest reference and yet hinge their entire sense of terror on the figment of Lovecraft’s canon that might lie directly out of view. The best stories in Swedish Cults are the opening tale, “The Furies from Boras,” “Happy Forever on Ostermalm,” and “Miss Witt’s Great Work,” but it’s worth noting that this is the majority of the full-length stories in this short volume and the little “Fragments” that sit between entries are a perfect structural addition to give the book the coherence it needed to hit with aplomb. The best stories in The Black Maybe are “The Time Remaining” and “Walks Among You,” though the entire book is fabulous. Just before these I read the first volume of the Valancourt’s International Horror series, which collects authors from around the world with a brief biography and a fantastic selection. Every one of these books is hard to ignore, and also A Different Darkness and Other Abominations by Luigi Musolino, which I read shortly after its 2022 release, they are making their mark simply by giving English readers access to a world beyond their market.

But what I would first recommend is their Valancourt Book of World Horror vol. 1 collection, which is designed to give you a picture of what is out there and is a fantastic array of some incredible foreign horror. The best stories include "The Time Remaining" by Attila Veres (not also found in his solo collection), "Uironda" by Luigi Musolino (also found in his solo book from Valancourt), "The Angle of Horror" by Cristina Fernández Cubas, "All the Birds" by Yvette Tan, "Kira" by Martin Steyn, and "Snapshots" by Jose María Latorre.

The 2025 releases have also been overall stellar as the months move along. One book that I think has already been forgotten — maybe because of the freshness of the author and the odd tilt of the title — is Beta Vulgaris by Margie Sarsfield. The book follows a young couple, told primarily through the woman’s anxiety-driven self-narration, as they leave their Brooklyn apartment and head to a Wisconsin sugar beet harvest to make a little money.

Subscribe to the newsletter

Strange occurrences begin to stack up, often involving beets that seem to pulsate and inject thoughts directly into your cerebellum, as staff disappear — including Tom, the boyfriend who cosplays as a broke punk while ignoring a sizable trust fund. The book is, overall, a pretty biting look at both the reality of class that sits underneath even loving romantic relationships and the way anxiety and depression can act as a monster growing in the corners of our mind, enacting real-world consequences in ways that can feel almost supernatural.

This is only Sarsfield’s second novel, and while there are moments when the monologue can feel a little too self-referential, it is ultimately a smart and quickly paced novel about the fear that almost all human contact carries, tracing its edge.

The Poorly Made and Other Things by Sam Rebelein was also high on the list for this year since it is a follow-up, though not exactly a direct sequel to, his 2023 book Edenville. Though inhabiting the same universe and region, it is a short-story collection that picks up on much of the mythology and yet ratchets up the genre inflection and energy so that each entry packs a punch on its own. While each story really does exist on their own terms, this feels like a complete work and I recommend reading it front to back rather than jumping between stories. Tk tk are the best. I will continue to say that Rebelein is amongst the most enjoyable, née fun, emerging horror authors of the decade and I am excited to see what comes after he chooses to leave Edenville.

Yet what I’m already seeing hit the most top ten lists for horror novels midway through 2025 (besides Stephen Graham Jones’s The Buffalo Hunter Hunter) is Nat Cassidy’s When the Wolf Comes Home. The book offers very little insight into its central premise — a choice likely made to avoid spoiling the first hundred pages — but it’s ostensibly branded as, perhaps, a werewolf novel. Cassidy is one of the best genre authors of the last decade, with his novel Mary being a particularly great example. And while I liked When the Wolf Comes Home, it didn’t hit with the same punch as his earlier work.

Likely in an effort to reach a broader market, the book feels as though it focuses on pacing and plot at the expense of fully realized characters or ingenuity. Much of it seems drawn from the storytelling model of 1990s thriller films rather than the kind of introspection and slow build that horror novels often use to form a deeper connection with readers. Around three-quarters of the way through, the novel’s effectiveness begins to drag, particularly because the actual dynamics of the premise leave such gaping holes in logic that they become hard to ignore. The ending has proven divisive, but I actually felt it brought things to as satisfactory a close as was possible. And alongside Cassidy’s trademark afterward, it ultimately brought my opinion back around.

One of the volumes I was most excited for this year was broken up by Amazon into five separate short stories, each offered to Kindle Unlimited subscribers as entries in The Shivers collection. This includes “The Blanks” by Grady Hendrix, “The Indigo Room” by Stephen Graham Jones, “Jacknife” by Joe Hill, Night and Day in Misery by Catriona Ward, and “Letter Slot” by Owen King — with Hendrix and Hill’s entries likely the best of a largely stellar collection. This remains one of the actually positive Amazon contributions to the genre, as it has forced big-name horror authors to continue churning out relatively long, prestige short stories, offering professional content to counterbalance the AI dreck starting to glob up the Kindle Unlimited library.

Picks and Shovels isn’t a genre book itself, but since its author, Cory Doctorow, is such a speculative fiction favorite, it felt wrong not to include it. It’s another stellar entry in the Martin Hench series, which follows a forensic accountant (it’s much more interesting than it sounds) as he starts his career in 1980s Silicon Valley and partners with a group of women bent on breaking the illegal monopoly a trio of clerics have created to grift their pious followers. The book is the longest and set the earliest in the Hench stories, and it takes the reader through the actual rhythms and logistics of the tech world with a certain seamless energy that only a kind of aspirational joy in the author could create — I actually started to see spreadsheets and motherboards as things of aesthetic beauty.

This arrives just months after Doctorow’s last Hench book, The Bezzle, about pyramid schemes and private prisons. It’s hard to compare books like this, but The Bezzle was an almost perfect detective novel: tight, expertly plotted, and sharply written. Picks and Shovels takes a different, more macro approach to storytelling and ratchets the pace down a bit. While I would ultimately pick The Bezzle as the best of the series, I highly recommend going start to finish with all three of the Hench novels. It’s a great way to peer into the world of esoteric financials with the kind of fascination necessary to understand the predatory nature of the economic system our entire lives are predicated on.