Documenting the Resistance to Gentrification

I first met Andrew Lee as he rapidly facilitated a meeting of a briefly-lived group that had formed to continue the fight against the mass displacement caused by gentrification in Portland, Oregon’s inner city core. Many of neighborhoods that were previously the center of Black Portland since the first half of the 20th Century were now littered by craft retail outlets, vegan eateries, and pop up cocktail bars, and a new set of property values and medium-rise condos came with them. The project was called Housing is for Everyone (HIFE), part of a post-Occupy effort by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) to pick up on the community energy, particularly around housing, and move into the world of community organizing with union resources. IF their low wage workers, such as homecare workers, were facing economic problems when they were looking for affordable housing, then a union should step beyond the shop floor to continue the fight. Class struggle takes place across the whole of our lives, not just one venue.

But like many projects, it lived briefly when it failed to generate steam once the resources were pulled out, and I, and Andrew, were back to thinking through housing through other projects. This led to work with the Portland Solidarity Network, re-establishing connections to the Take Back the Land movement, and other autonomous housing projects, sometimes reconvening the same group of people to take on momentary threats of eviction. All of this was foundational to the growth of a new class of housing organizing, particularly the formation of the Portland Tenants United tenants union, a founding member of the national Autonomous Tenants Union Network. While I stayed in Portland, Andrew moved down to the Bay to continue organizing, then to Philadelphia, which is seeing its own transition from the image of the (nearly) affordable East Coast city to a priced-out super metropolis in the model of New York City just an hour away.

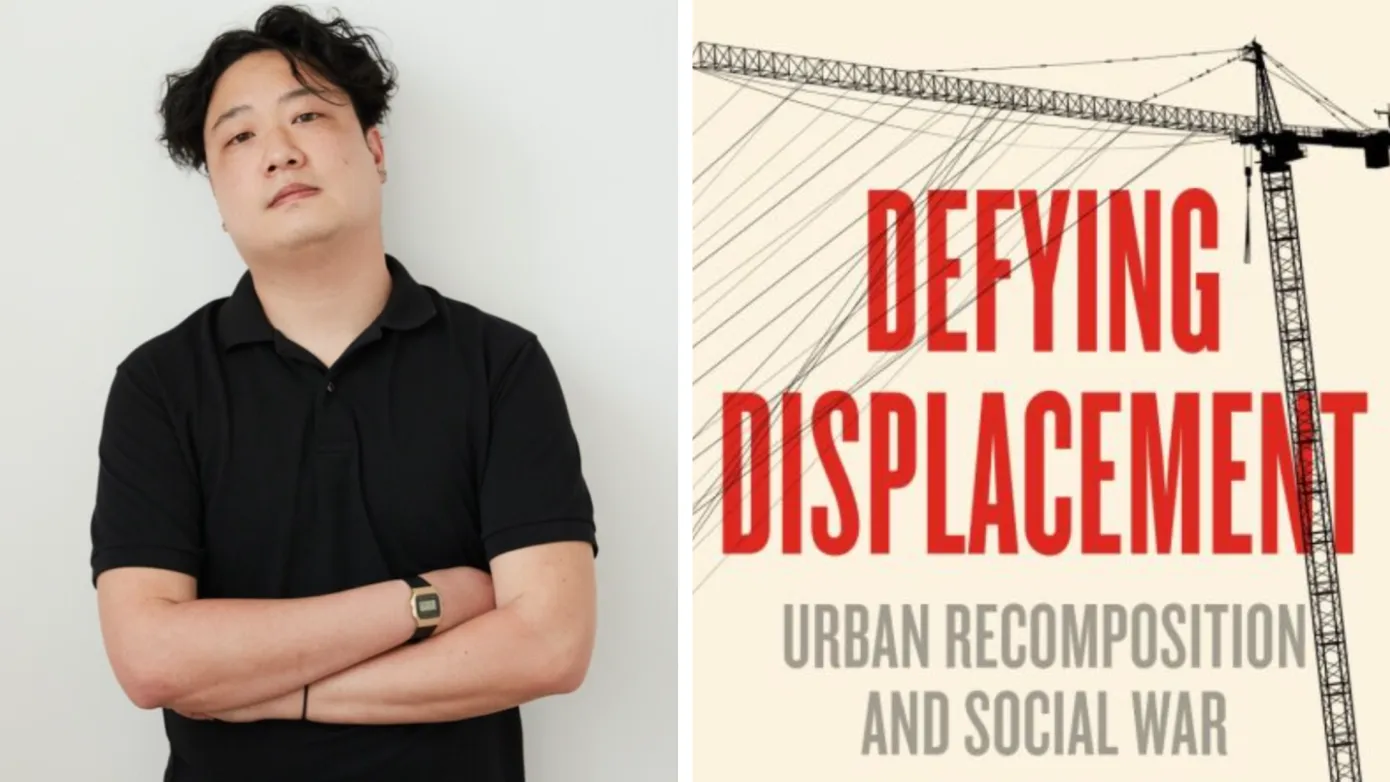

In his new book, co-published with AK Press and the Institute for Anarchist Studies, Defying Displacement: Urban Recomposition and Social War, Andrew talks through the organizing reality of confronting housing as both a commodity and a human necessity. We talk through the changing nature of city housing, the problems with most progressive approaches to dwindling affordable housing access, and consider the opportunities that direct action provides when conceptualizing housing not just as a resource to fight for but as a battlefield in the class war.

Shane Burley: How would you explain gentrification to someone uninitiated, and how do we move beyond what you describe as a consumer-oriented critique? Who is really responsible as neighborhoods gentrify?

Andrew Lee: Gentrification is the economic displacement as neighborhoods are targeted for intensive capital investment to accommodate wealthier residents. Urban neighborhoods of color are the most “profitable” to gentrify, since owner-occupied homes in Black US neighborhoods are undervalued by an average of $48,000. This means a housing speculator can make tens of thousands of dollars simply with the changing racial composition of a neighborhood through forced displacement. Gentrification is a positive policy objective for corporations, universities, transnational financial institutions, and local political elites. A discourse which ends with the desire of an individual gentrifier to live in a certain neighborhood has the same limitations as any other variety of ethical consumerism: namely, it risks missing the economic and political forces that structure the market within which individual consumer preferences occur.

SB: What role does "liberated space," such as housing occupations and blockades, bloc parties, squats, social centers, and the like have in building a mass movement against displacement? How do they work alongside other types of tactics that progressives focus on, like advocating for rent control or increased low-income housing?

AL: If we’re serious about not simply slowing down but actually stopping contemporary urban displacement—truly building secure, community-controlled neighborhoods to give to coming generations—we need to decommodify land, to remove it from the speculative market. Community land trusts, squats, and housing occupations all take land off the housing market, thereby creating the possibility of autonomous, democratic land use. Strategically, spaces like block parties and social centers serve as nuclei of resistance, centers of attraction operating against the centrifugal force of community dispersal.

Subscribe to the newsletter

SB: What are the limits of the supply argument for affordable housing that is so typically found in the YIMBY crowd?

AL: “Yes in My Backyard” ideologues argue that housing costs will only decrease if we increase housing supply across the board. They promote new housing development of all types, including market-rate housing—in the gentrifying city, this means housing marketed to gentrifiers. This argument makes intuitive sense, but only if you believe incorrectly that all housing units are essentially interchangeable, or fungible, goods. In reality, virtually every city meets and exceeds its goals for market-rate housing construction, and even overheated real estate markets like the San Francisco Bay Area have many times as many vacant units as unhoused people. The YIMBY political line is particularly nefarious because it’s saying that the only people who can fix housing unaffordability are the people who engineer and profit from it—developers, landlords, and real estate investors. To truly address displacement we need to confront, not reinforce, the financialization of housing and the reign of capital over community composition and survival.

SB: How does precarious housing relate to precarious work, and how can we connect labor and housing struggles to become congruent? Is this a question of building out union structures outside the workplace, a kind of community syndicalism, or are we seeing housing as its own completely distinct terrain of class subjectivity?

AL: Displacement is profitable because of a transformation in contemporary capitalism which incentivizes the concentration not of an urban industrial working class—whose members included previous generations of currently-gentrifying neighborhoods before outsourcing, automation, and deindustrialization—but a much smaller caste of highly-educated, highly-paid professionals, owners, and technicians working in tech, biotech, finance, real estate, and elite universities. They are pulled together in large firms, as on tech or university campuses, while low-wage workers are more likely to work at small businesses, as independent contractors, or in the informal economy. This situation is diametrically opposed, both spatially and industrially, to the proletarian urbanization and industrial concentration of the Second Industrial Revolution. For this reason, we ought to expand our tactical and strategic visions beyond those developed in that preceding epoch. As I wrote in a piece for Notes from Below which was an embryonic form of my book, “If the role of the political organization in industrial capitalism was to connect and generalize the strike, what are the concrete actions it must connect and generalize today?”

SB: What is this concept of counter-insurgency, and how does it relate to mass displacement? How does the rapidly accelerating carceral state relate to the transformations of neighborhoods?

AL: Modern counter-insurgency, the framework of military and social intervention designed to prevent civilian discontent from blooming into an insurgent, proto-revolutionary situation, was first elaborated during the Vietnam War before being almost immediately applied to combat urban unrest in American cities.

The counter-insurgency framework sees both the repressive force of the police and the military and the cooperatative force of civil society patronage and social services used as tools to separate potential insurgents from community support. Consider how state elites deployed military and paramilitary force against protesters during the 2020 George Floyd Uprising at the same time as millions of dollars flowed to non-profits and politicians loudly promised (largely illusory) reforms.

We see a similar dynamic in gentrifying cities. Elites work to actively construct gentrification to create “superstar cities”: cities with high levels of displacement in favor of highly-paid professional workers. Their approach to the existing communities is therefore best understood not through the framework of democratic engagement but that of counter-insurgency, with the ruling class trying to manage and diffuse popular resistance as it engineers mass displacement.

Subscribe to the newsletter

SB: How are liberal politics, often in the form of the DEI infrastructure, being used to undermine direct action struggles around housing?

AL: The sponsors of gentrifying mega-projects like major tech firms and universities loudly proclaim their commitments to diversity and equity—when it suits their interests. The question is equity for whom? Gentrification targets Black and brown neighborhoods for removal, with these institutions invariably having dismally low levels of Black and Latinx representation. And it’s women and gender minorities, queer people, and disabled people who are exposed to the greatest harm when their neighborhoods gentrify. That would remain the case no matter how many people from a certain identity or background are “represented” among the gentrifiers. An institution profiting from mass displacement is inherently oppressive along all axis of power.

SB: How can movement chart a path around both class reductionism and liberal representationalism? What are the contours of our emerging class politics, and how are they different from decades previously?

AL: The most militant actually existing struggles around class in a multitude of cities around the world are taking the form of resistance to gentrification. These fights are deeply gendered and racialized as well as fundamentally grounded in the relationships distinct communities have to contemporary capitalist production. A class politics that flattens these struggles by observing that a software engineer and the precariously employed elder he displaces are both, in a sense, workers is, in my opinion, neither useful nor materialist. Similarly, identity politics which end at the inclusion of a certain percentage of an identity group within an elite caste that profits from the dispossession of the vast majority of members of that group cannot be considered properly anti-racist, feminist, etc.

SB: What is the “social war” referenced in the book title?

AL: We should be clear that gentrification is not an accidental process: it’s an intended, positive policy outcome for local government and a condition of production for the wealthiest firms in contemporary capitalism. Mass displacement is only possible with the threat of state violence, which in the contemporary US includes police departments armed with literal military weapons. Breonna Taylor was murdered by Louisville police because they believed her ex-partner, an accused drug dealer, was the “primary roadblock” to a billion-dollar neighborhood “revitalization” project. The local governments’ deployment of counter-insurgent practices to diffuse anti-displacement resistance is a tacit admission of a state of war: a low-level war of elimination against the residents of potentially-profitable neighborhoods.

This social war is a class war, but I share J. Sakai’s bewilderment that “whenever Western radicals hear words like ‘unions’ and ‘working class’ a rosy glow glazes over their vision, and the ‘Internationale’ seems to play in the background.” Because our theoretical and historical guidestones come to us from the nineteenth-century era of mass proletarianization, we’re often predisposed to think of class struggle as uniting all working people—irrespective of any other social determinants—in a community of interests. A white professor and an immigrant dishwasher may both be workers, but they find themselves on opposing sides of the struggle around gentrification: perhaps the most productive arena of class struggle in the contemporary economy.

SB: What are movements or organizations existing right now that you think are on the front lines of confronting displacement? What strategies or tactics make them distinct?

AL: The collaboration between the Black residents of the People’s Townhomes in West Philly and the Philadelphia Chinatown residents also fighting displacement are extremely encouraging to me, as is Decolonize Philly’s work bringing different land justice organizations together in conversation with one another. We need to remember that the far goal if we are to create enduring, resourced communities is to abolish the capitalist and colonialist property relations which allow for economic displacement, as well as to actively engage in the hard work of constructing intercommunal solidarity against the beneficiaries of the gentrification economy.