Horror at the End of 2025

In my own experiment with writing slightly longer and more involved analysis of this year’s reading, I ultimately just wrote less. Still, this was a year in which common themes ran through much of what I encountered, particularly in new books that acted as an accurate temperature check for where we are at.

In our current horror golden age, the real boom is around New Queer Horror, particularly from trans authors who are creating new spins on body and cosmic horror, while also expanding the cast of untrustworthy characters that often sit beneath the social conditions of these narratives. This year, both Grace Byron and Bitter Karella stood out, publishing Herculine and Moonflow, respectively. Herculine is an incredible step forward for Byron, who is still new in her career, as is Karella. The novel follows a trans character meeting an ostensible girlfriend in a commune for trans women, a space that slowly surrenders to an overarching occult reinterpretation of transition and protection. The book is a classic work of cult horror, but it carries a familiarity and relatability that makes it even more haunting. I felt at home inside the cult, and I could feel the experiences that drove people there.

A different kind of cult sits at the heart of Karella’s Moonflow, one that blends humor with legitimate folk horror and a Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminist spin. The book avoids caricature and instead realizes the real fear that this world of gynocentric feminism can inspire. Our lead travels into the Northern California forest to help a friend from an earlier support group find psychedelic mushrooms, only to descend into a feminist goddess cult that venerates cyclical womanhood and uses fungi to tap into the earth’s cosmic energy, all with plenty of jokes, sex, and schlocky horror moments along the way. I read both books in a matter of days, and each registered identity and experience in ways that deepened the genre themes rather than overwhelming them.

Just before that, I finally picked up two slightly older works often spoken of in the same breath.

Alison Rumfitt has become something of a scion of New Trans Horror over the past few years since releasing her incredible debut novel, Tell Me I’m Worthless. At its core, the book is a haunted house story, one that roots the horrors of a building in the legacies of British colonialism and the rise of cultural fascism across England. Rumfitt’s prose is nearly ecstatic and close to stream of consciousness, taking multiple characters into conflict with one another while privileging internal monologues over the mundane events of reality. Beneath this, an act of cruel abuse sits largely unseen, driving a rift between two characters, one of whom turns toward violent transphobia while the other struggles to understand their own trauma and mental health needs.

The novel reads as a treatise on fascism, particularly through its metapolitical understanding of how fascism takes root, drawing implicitly on Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of microfascism. This makes Rumfitt’s follow-up novel, Brainwyrms (2023), a fitting continuation. It uses the escalation of British transphobia as the backdrop for a story about alien parasites that transform potentially kind humans into murderous, chaotic figures, sometimes sexual, sometimes grotesque. The book is strongest when it leans into a more pronounced narrative, something it avoids for long stretches in the middle. Rumfitt is not a plot-driven author, and it is easy to get lost in extended monologues, distant memories, and observations that feel disconnected from the book’s structure. Still, this rarely matters. Both novels are so immersive that you accept the writing on its own terms. While the label New Trans Horror gets applied broadly, there is little stylistically binding these novels together beyond the identities of their authors, though the shared fears and pressures of the moment are clearly present on the page.

Similarly, Hayley Piper’s latest novel retrofits the established cosmology of cosmic horror into a queer S and M love story. The Game in Yellow adapts Robert Chambers’ The King in Yellow to tell the story of a couple losing stability as they discover a play that intensifies their masochistic escapism. Chambers’ world fits unusually well here, likely due to Piper’s ability to channel a contemporary Lovecraftian tone while also navigating the troubling dynamics of the central relationship and the histories the characters bring into their conflict. Though desolate, the book has a quiet brilliance, and it helps carry forward how we think about classic works like Chambers’ and their relevance to modern cosmic dread.

I also made an effort to continue bringing in both classic and international horror, finally reading William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist. While it still appears on most lists of the scariest novels of the last fifty years, it is rarely framed as the mystery thriller it actually is. In this way, it has more in common with Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby than with straightforward devil narratives. We follow a parish priest piecing together fragments of a story as we slowly descend into the heart of evil, something only hinted at early in the book. It reads as a popular, modern novel, reminding me how much contemporary horror has become shaped by subcultural presses and arthouse sensibilities, which is not a criticism.

Blatty wrote The Exorcist in part due to his own fervent Catholicism, hoping to scare people into fearing the Devil as deeply as he believed they should. In later years, he even sued Georgetown University, a Catholic institution, for what he saw as insufficient opposition to abortion. Yet the novel remains masterful in its handling of form, its sharp pacing, and its ability to create profound empathy for characters who reveal themselves only in fragments.

More recently, I turned to Sara Gran’s Come Closer, another fixture on must-read horror lists. It belongs there. At just 120 pages, it feels like a perfect horror novel, with not a word wasted. Like The Exorcist, it is a possession story, but one that chronicles the dissolution of a closed relationship as one partner becomes unrecognizable to the other. This is where horror works best, when the supernatural is grafted onto experiences we already understand. The frightening myth gains power when it comments emotionally on things that facts and discourse cannot fully capture.

The same is true of Jac Jemc’s The Grip of It, a haunted house novel that more accurately tells the story of a marriage falling apart. A couple moves from an unnamed city into the countryside and buys a house shortly after the man suffers a major loss tied to his gambling addiction. The house intrudes into their bodies and psyches, leading to impulsive behavior and shocking acts of graffiti. What makes The Grip of It effective is its disorientation, which places you directly behind the eyes of the characters. A haunted house would be confusing, dysregulating, and alienating more than thrilling, and the novel captures the devastation that illness or abuse can wreak on a relationship. Who is responsible? Where does the harm come from? Is it you, or is it me?

Continuing my trend towards film horror was The October Film Haunt by Michael Wehunt, which tells the story of a film blogger who suggests readers enact an urban legend related to a cult film. When one young follower dies doing so, the bloggers scatter, and a decade later film fans, acting out a possible sequel to the original cult hit, are killing those around her, and there may be a demonic source creeping behind the celluloid. The book is itself a little fragmented and could have been condensed a tiny bit, but it maintains the sense of mysticism about horror films in ways familiar to Paul Tremblay’s Horror Movie, Silvia Moreno-Garcia's Silver Nitrate, or even Gretch Felker-Martin's Blake Flame from earlier this year, and I think it’s worth a read for those who like the film-literary crossover.

This was a year of heavy travel, and I tried to match some of my reading to where I was. While in Scotland, I read three books by hometown author David Sodergren, who writes pulp-friendly horror set in the desolate reaches of Scotland’s northern edge. The Haar, the best of the three, follows a coastal town being bulldozed by a wealthy developer, possibly an American building golf courses. The story centers on an aging woman with few friends and a long-dead husband. When a creature washes ashore that can temporarily heal her and even embody her lost love, it sparks a form of resistance against the billionaire encroaching on the town. Almost as intriguing is Rotten Tommy, a pleasantly bizarre novel about a lost children’s show hidden in a remote village populated by puppets and mythological outcasts. It reminded me of Neil Sharpson’s Knock Knock, Open Wide, one of my favorite books of 2023. I also started Francine Toon's brilliantly bleak and haunting folk horror novel Pine, set along the same upper crest of Scotland running from Inverness to Isle of Skye, which would be a high recommendation even for those not taken with genre fiction.

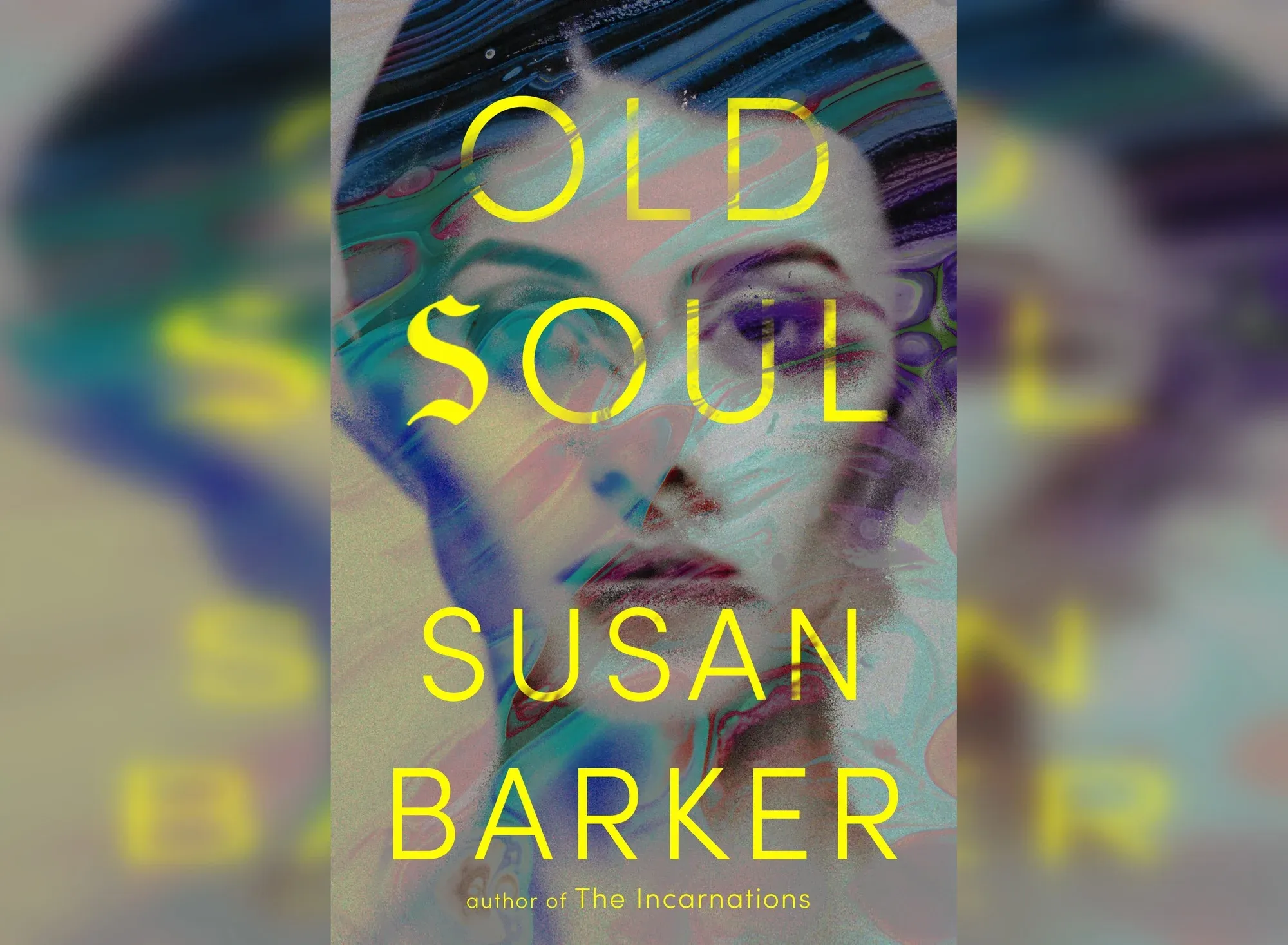

When I arrived in Ireland, I picked up Sharpson’s newest novel, set on a remote Irish island and built around a mythological figure at the center of a micro-society. I cannot say much without spoiling it, but while enjoyable, it felt less substantial than Knock Knock, Open Wide. In Belfast, I also picked up the 2024 British horror anthology Of the Flesh, recently released in paperback, which opens with a breathtaking story by Susan Barker about a mistress haunted by the dead wife of her lover.

This was not a particularly strong year for short horror anthologies, at least among those I read, though Ellen Datlow’s experimental Night/Day was worth attention. The book has two covers and two sets of stories, one inverted, divided between day and night settings. The distinction was not always clear, but the anthology featured a strong lineup. Standouts included “Hold Us in the Light” by A. C. Wise, “The Wanting” by A. T. Greenblatt, “The Bright Day” by Riya Sharma, “The Night House” by Gemma Files, “Fear the Dark” by Benjamin Percy, and my favorite, “Secret Night” by Nathan Ballingrud. While the concept suggested that day could be as frightening as night, the nocturnal stories ultimately felt stronger. I also turned back to two collections from 2024, this time collections of novellas, one by Josh Malerman’s Spin the Black Yarn, which was hit or miss with stories that felt more like surreal fairy tales than horror, and Three Miles Past by Stephen Graham Jones, which was also a mix and leaned again into his slasher obsession. Short fiction anthologies and collections are, by their very nature, hard to remain consistent with, and I usually skip one or two, so with novella collections it can be even more difficult given that the story that fails to connect can run a hundred pages.

What I spent more time with this year, and hope to continue exploring, were small press horror magazines and journals. There are surprisingly many of them. For anyone who has written professionally, there are few ways to make stable income outside of short journalism or opinion writing. Fiction has never fully developed a sustainable online model unless tied to larger non-fiction publications, which keeps print magazines central to short horror fiction. I returned to Weird Horror, now in its fifth year as an unlikely success from Undertow Publications, though it is clearly under financial strain. In the Winter 2025 issue, the editor announced the removal of reviews and page art to keep the magazine viable. Cosmic Horror Monthly is a newer publication filling part of the gap left by the decline of Lovecraft E-Zine, though its lineup has been uneven. The standout this year was Chthonic Matter Quarterly, which featured a strong slate of stories, including one by anarchist speculative fiction author Lara Messersmith-Glavin, delivering cosmic horror directly into a haunted house narrative.

Like most horror readers, I also picked up Stephen Graham Jones’ The Buffalo Hunter Hunter, likely his most celebrated novel since The Only Good Indians. As a period piece set around the turn of the twentieth century, I felt mixed about the setting and language, though that reflects my own literary preferences more than the book’s quality. I started it with plans to finish after the new year, alongside Philip Fracassi’s The Boys in the Valley, a ghost story set in an orphanage. Jones’ stream of consciousness style can obscure major narrative events, demanding close attention to parse its subtleties. Fracassi’s work, by contrast, benefits from a clean, accessible prose style, likely shaped by his background in screenwriting.

This accessibility is also what makes Fracassi’s novels dependable. I rarely miss one, because he delivers what many readers want from mainstream horror: clear writing that grounds characters and events before introducing unpredictable threats. Horror can either unsettle through experimental prose or through familiar narrative forms, and both approaches are valid. Fracassi excels at the latter, often sliding abruptly into moments of stark madness. His 2025 novel, The Autumn Springs Retirement Home Massacre, became a USA Today bestseller, which was somewhat surprising given how conventional it is. The novel blends slasher tropes and mystery, following a seventy-eight-year-old final girl in a retirement home who must uncover the killer to protect her friends and her independence. It is clever and readable, but at nearly four hundred pages, it could have been significantly shorter. We are clearly in a slasher renaissance, driven by nostalgia for 1980s genre fare, and while it is enjoyable to see a skilled writer execute a familiar form, I will be hoping for greater distinction in Fracassi’s work in 2026.

The opposite could be said about Augustina Bazterrica's work, notably short and taken with flights of narrative dissolution and surrealism. Her 2025 novel The Unworthy was amongst the most mentioned of the year, and follows a woman questioning her life in an austere cult set along a post-apocalyptic desert of a world surrounding it. The book is seldom grounded to a relatable set of events, and so you have to abandon that expectation right from the start if you hope to follow it through. I couldn’t help but feel as though the novel could have been helped either by extension and added detail or to simply truncate it to a novella or novelette. Her 2024 collection Nineeen Claws and a Black Bird feels well bonded to The Unworthy, particularly in the fact that while this is marketed as horror (and it, of course, is), it was not likely written with American genre market conventions in mind, meaning that it will ultimately be hit and miss if you enter with that expectation. But given the success she has had in the American genre world, and the recent surge that Latin and South american horror has had, she is clearly doing something right that the rest of hte publishers (and readers) will hae to catch up to. It sould also be noted that there is a deep threat of anti-imperialist and feminist characterization across her work, a new type of religious criticism, and she sits alongside Mariana Enriquez and Amanda Lima as Latin American authors writing in a largely American literary world (and whose work starkly akncowledges it) who are playing at the edge of genre limitations and even creating bridges between short and long-form fiction. Last year’s A Sunny Place for Shady People (which I mostly read this year) and Craft: Stories I Wrote for the Devil (something I reviewed last year) should also remain high on your “to read” pile.

Just as is currently happening with feature films, the average length of books has grown in ways that often outstay their welcome. A number of horror novels in recent years have felt as though they could have cut the length by a third, in half, become a novella, or gone even shorter. This is my only real criticism of the cosmic horror novel The Faceless Thing We Adore, about a woman leaving her claustrophobic romantic relationship and mundane life and ending up on a distant island with a group of homesteaders connected to a possible entity they meet in a cave. The book itself has several profound evolutions in the setting and characters, so I’ll avoid with the spoilers, but particularly later in the novel certain developments drag and it could have used a closer cropping on it’s total wordcount (I will add, however, the book design was brilliant with beautiful art adorning the edges of the pages themselves). At the same time a number of novels with brilliant ideas and style felt hard to complete, such as Red Rabbit Ghost, a generally well written Southern Gothic novel that felt a little longwhinded, was easy to get lost in teh characters and widning plot, and ultimately rested on a rather mundane set of character mysteries. Similarly, Passing Through a Prarie Country, a promising indigenous ghost story was hard to launch in, partially because it avoided genre tropes so sufficiently that it never really raised the stakes on teh supernatural horror at it’s core. The book is still well written by a very promising author and just one more signal of the incoming popularity of indigenous horror, something that has been present for years within the horror inner circle and is now having another crossover point to the mainstream literary world. Currently, the indigenous “dark fiction” anthology Never Whistle at the Night from 2023 remains a bestseller, a great sign for what’s to come.

As with the past few years, I kept the reading recent, in part to be able to write about it, and I’ll continue that next year with a greater focus on graphic fiction/comics, short horror, and modern classics. I also expect to pick one particularly epic piece of recent horror writing on here, perhaps Joe Hill’s recent near 1,000 page magnum opus, King Sorrow. I will also be publishing quite a bit more on Jewish horror, including a reading list of both novels and short fiction with a lean away from Israeli/Zionist horror since that is often the only Jewish horror we end up with and often strips the distinctly Jewish elements out of it.

If you like these literary interludes, please reach out and share online and perhaps we can work out a radical horror reading group. Stay tuned as I announce a genre fiction project I am already in the works on this year and hopefully we can help create a larger world of anarchist horror and SF!

In my own experiment with writing slightly longer and more involved analysis of this year’s reading, I ultimately just wrote less. Still, this was a year in which common themes ran through much of what I encountered, particularly in new books that acted as an accurate temperature check for where we are at.

In our current horror golden age, the real boom is around New Queer Horror, particularly from trans authors who are creating new spins on body and cosmic horror, while also expanding the cast of untrustworthy characters that often sit beneath the social conditions of these narratives. This year, both Grace Byron and Bitter Karella stood out, publishing Herculine and Moonflow, respectively.

Herculine is an incredible step forward for Byron, who is still new in her career, as is Karella. The novel follows a trans character meeting an ostensible girlfriend in a commune for trans women, a space that slowly surrenders to an overarching occult reinterpretation of transition and protection. The book is a classic work of cult horror, but it carries a familiarity and relatability that makes it even more haunting. I felt at home inside the cult, and I could feel the experiences that drove people there.

A different kind of cult sits at the heart of Karella’s Moonflow, one that blends humor with legitimate folk horror and a Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminist spin. The book avoids caricature and instead realizes the real fear that this world of gynocentric feminism can inspire. Our lead travels into the Northern California forest to help a friend from an earlier support group find psychedelic mushrooms, only to descend into a feminist goddess cult that venerates cyclical womanhood and uses fungi to tap into the earth’s cosmic energy, all with plenty of jokes, sex, and schlocky horror moments along the way. I read both books in a matter of days, and each registered identity and experience in ways that deepened the genre themes rather than overwhelming them.

Just before that, I finally picked up two slightly older works often spoken of in the same breath.

Alison Rumfitt has become something of a scion of New Trans Horror over the past few years since releasing her incredible debut novel, Tell Me I’m Worthless, which I wrote about earlier. Both of her novels are so immersive that you accept the writing on its own terms. While the label New Trans Horror gets applied broadly, there is little stylistically binding these novels together beyond the identities of their authors, though the shared fears and pressures of the moment are clearly present on the page.

Similarly, Hayley Piper’s latest novel retrofits the established cosmology of cosmic horror into a queer S and M love story. A Game in Yellow adapts Robert Chambers’ The King in Yellow to tell the story of a couple losing stability as they discover a play that intensifies their masochistic escapism. Chambers’ world fits unusually well here, likely due to Piper’s ability to channel a contemporary Lovecraftian tone while also navigating the troubling dynamics of the central relationship and the histories the characters bring into their conflict. Though desolate, the book has a quiet brilliance, and it helps carry forward how we think about classic works like Chambers’ and their relevance to modern cosmic dread.

I also made an effort to continue bringing in both classic and international horror, finally reading William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist. While it still appears on most lists of the scariest novels of the last fifty years, it is rarely framed as the mystery thriller it actually is. In this way, it has more in common with Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby than with straightforward devil narratives. We follow a parish priest piecing together fragments of a story as we slowly descend into the heart of evil, something only hinted at early in the book. It reads as a popular, modern novel, reminding me how much contemporary horror has become shaped by subcultural presses and arthouse sensibilities, which is not a criticism.

Blatty wrote The Exorcist in part due to his own fervent Catholicism, hoping to scare people into fearing the Devil as deeply as he believed they should. In later years, he even sued Georgetown University, a Catholic institution, for what he saw as insufficient opposition to abortion. Yet the novel remains masterful in its handling of form, its sharp pacing, and its ability to create profound empathy for characters who reveal themselves only in fragments.

More recently, I turned to Sara Gran’s Come Closer, another fixture on must-read horror lists. It belongs there. At just 120 pages, it feels like a perfect horror novel, with not a word wasted. Like The Exorcist, it is a possession story, but one that chronicles the dissolution of a closed relationship as one partner becomes unrecognizable to the other. This is where horror works best, when the supernatural is grafted onto experiences we already understand. The frightening myth gains power when it comments emotionally on things that facts and discourse cannot fully capture.

The same is true of Jac Jemc’s The Grip of It, a haunted house novel that more accurately tells the story of a marriage falling apart. A couple moves from an unnamed city into the countryside and buys a house shortly after the man suffers a major loss tied to his gambling addiction. The house intrudes into their bodies and psyches, leading to impulsive behavior and shocking acts of graffiti. What makes The Grip of It effective is its disorientation, which places you directly behind the eyes of the characters. A haunted house would be confusing, dysregulating, and alienating more than thrilling, and the novel captures the devastation that illness or abuse can wreak on a relationship. Who is responsible? Where does the harm come from? Is it you, or is it me?

Continuing my trend toward film horror was The October Film Haunt by Michael Wehunt, which tells the story of a film blogger who suggests readers enact an urban legend related to a cult film. When one young follower dies doing so, the bloggers scatter, and a decade later film fans, acting out a possible sequel to the original cult hit, are killing those around her, and there may be a demonic source creeping behind the celluloid. The book is a little fragmented and could have been condensed slightly, but it maintains the sense of mysticism about horror films in ways familiar to Paul Tremblay’s Horror Movie, Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s Silver Nitrate, or even Gretch Felker-Martin’s Blake Flame from earlier this year.

This was a year of heavy travel, and I tried to match some of my reading to where I was. While in Scotland, I read three books by hometown author David Sodergren, who writes pulp-friendly horror set in the desolate reaches of Scotland’s northern edge. The Haar, the best of the three, follows a coastal town being bulldozed by a wealthy developer, possibly an American building golf courses. The story centers on an aging woman with few friends and a long-dead husband. When a creature washes ashore that can temporarily heal her and even embody her lost love, it sparks a form of resistance against the billionaire encroaching on the town. Almost as intriguing is Rotten Tommy, a pleasantly bizarre novel about a lost children’s show hidden in a remote village populated by puppets and mythological outcasts. It reminded me of Neil Sharpson’s Knock Knock, Open Wide, one of my favorite books of 2023. I also started Francine Toon’s brilliantly bleak and haunting folk horror novel Pine, set along the same upper crest of Scotland running from Inverness to the Isle of Skye, which I would highly recommend even to those not taken with genre fiction.

When I arrived in Ireland, I picked up Sharpson’s newest novel, The Burial Tide, set on a remote Irish island and built around a mythological figure at the center of a micro-society. I cannot say much without spoiling it, but while enjoyable, it felt less substantial than Knock Knock, Open Wide. In Belfast, I also picked up the 2024 British horror anthology Of the Flesh, recently released in paperback, which opens with a breathtaking story by Susan Barker about a mistress haunted by the dead wife of her lover.

This was not a particularly strong year for short horror anthologies, at least among those I read, though Ellen Datlow’s experimental Night/Day was worth attention. The book has two covers and two sets of stories, one inverted, divided between day and night settings. The distinction was not always clear, but the anthology featured a strong lineup. Standouts included “Hold Us in the Light” by A. C. Wise, “The Wanting” by A. T. Greenblatt, “The Bright Day” by Riya Sharma, “The Night House” by Gemma Files, “Fear the Dark” by Benjamin Percy, and my favorite, “Secret Night” by Nathan Ballingrud. While the concept suggested that day could be as frightening as night, the nocturnal stories ultimately felt stronger. I also returned to two novella collections from 2024, Josh Malerman’s Spin the Black Yarn, which was hit or miss with stories that felt more like surreal fairy tales than horror, and Stephen Graham Jones’ Three Miles Past, which leaned again into his slasher obsession.

What I spent more time with this year, and hope to continue exploring, were small press horror magazines and journals. There are surprisingly many of them. For anyone who has written professionally, there are few ways to make stable income outside of short journalism or opinion writing. Fiction has never fully developed a sustainable online model unless tied to larger non-fiction publications, which keeps print magazines central to short horror fiction. I returned to Weird Horror, now in its fifth year as an unlikely success from Undertow Publications, though it is clearly under financial strain. In the Winter 2025 issue, the editor announced the removal of reviews and page art to keep the magazine viable. Cosmic Horror Monthly is a newer publication filling part of the gap left by the decline of Lovecraft E-Zine, though its lineup has been uneven. The standout this year was Chthonic Matter Quarterly, which featured a strong slate of stories, including one by anarchist speculative fiction author Lara Messersmith-Glavin, delivering cosmic horror directly into a haunted house narrative.

Like most horror readers, I also picked up Stephen Graham Jones’ The Buffalo Hunter Hunter, likely his most celebrated novel since Only Good Indians. As a period piece set around the turn of the twentieth century, I felt mixed about the setting and language, though that reflects my own literary preferences more than the book’s quality. I started it with plans to finish after the new year, alongside Philip Fracassi’s The Boys in the Valley, a ghost story set in an orphanage. Jones’ stream-of-consciousness style can obscure major narrative events, demanding close attention to parse its subtleties. Fracassi’s work, by contrast, benefits from a clean, accessible prose style, likely shaped by his background in screenwriting.

This accessibility is also what makes Fracassi’s novels dependable. I rarely miss one, because he delivers what many readers want from mainstream horror: clear writing that grounds characters and events before introducing unpredictable threats. Horror can either unsettle through experimental prose or through familiar narrative forms, and both approaches are valid. Fracassi excels at the latter, often sliding abruptly into moments of stark madness. His 2025 novel, The Autumn Springs Retirement Home Massacre, became a USA Today bestseller, which was somewhat surprising given how conventional it is. The novel blends slasher tropes and mystery, following a seventy-eight-year-old final girl in a retirement home who must uncover the killer to protect her friends and her independence. It is clever and readable, but at nearly four hundred pages, it could have been significantly shorter. We are clearly in a slasher renaissance, driven by nostalgia for 1980s genre fare, and while it is enjoyable to see a skilled writer execute a familiar form, I will be hoping for greater distinction in Fracassi’s work in 2026.

The opposite could be said about Agustina Bazterrica’s work, notably short and taken with flights of narrative dissolution and surrealism. Her 2025 novel The Unworthy was among the most mentioned of the year, and follows a woman questioning her life in an austere cult set along a post-apocalyptic desert of a world surrounding it. The book is seldom grounded to a relatable set of events, and so you have to abandon that expectation right from the start if you hope to follow it through. I couldn’t help but feel as though the novel could have been helped either by extension and added detail or by truncating it to a novella or novelette. Her 2024 collection Nineteen Claws and a Black Bird feels well bonded to The Unworthy, particularly in that while this is marketed as horror and it certainly is, it was not likely written with American genre market conventions in mind. Given the success she has had in the American genre world, and the recent surge of Latin American horror, she is clearly doing something right that the rest of the publishers and readers will have to catch up to. It should also be noted that there is a deep thread of anti-imperialist and feminist characterization across her work, a newer type of religious criticism, and she sits alongside Mariana Enriquez and Amanda Lima as Latin American authors writing in a largely American literary world who are pushing at the edge of genre limitations and creating bridges between short and long-form fiction. Last year’s A Sunny Place for Shady People, which I mostly read this year, and Craft: Stories I Wrote for the Devil, something I reviewed last year, should also remain high on your to-read pile.

Just as is currently happening with feature films, the average length of books has grown in ways that often outstay their welcome. A number of horror novels in recent years have felt as though they could have cut the length by a third, in half, become a novella, or gone even shorter. This is my only real criticism of the cosmic horror novel The Faceless Thing We Adore, about a woman leaving her claustrophobic romantic relationship and mundane life and ending up on a distant island with a group of homesteaders connected to a possible entity they meet in a cave. The book has several profound evolutions in setting and character, so I will avoid spoilers, but particularly later in the novel certain developments drag and it could have used a closer crop on its total word count. At the same time, a number of novels with brilliant ideas and style felt hard to complete, such as Red Rabbit Ghost, a generally well-written Southern Gothic novel that felt a little long-winded. It was easy to get lost in the characters and winding plot, and it ultimately rested on a rather mundane set of character mysteries. Similarly, Passing Through a Prairie Country, a promising Indigenous ghost story, was hard to launch, partially because it avoided genre tropes so thoroughly that it never really raised the stakes on the supernatural horror at its core. The book is still well written by a very promising author and just one more signal of the growing popularity of Indigenous horror, something that has been present for years within the horror inner circle and is now crossing over into the mainstream literary world. The Indigenous dark fiction anthology Never Whistle at the Night from 2023 remains a bestseller, a great sign for what is to come.

As with the past few years, I kept my reading recent, in part to be able to write about it, and I will continue that next year with a greater focus on graphic fiction and comics, short horror, and modern classics. I also expect to pick one particularly epic piece of recent horror writing, perhaps Joe Hill’s near 1,000-page magnum opus King Sorrow. I will also be publishing more on Jewish horror, including a reading list of both novels and short fiction that leans away from Israeli or Zionist horror, which is often the only Jewish horror we end up with and often strips out distinctly Jewish elements.

If you like these literary interludes, please share them, and perhaps we can work out a radical horror reading group. Stay tuned as I announce a genre fiction project already in the works this year, and hopefully we can help create a larger world of anarchist horror and SF.