How Antifascists Remember the Holocaust

The alt-right may not have become a known term until 2015, but early on there were major controversies centering on movement founder Richard Spencer. The first was reported by MSNBC host Rachel Maddow that singled out an article by British white nationalist Colin Liddell on Spencer’s AlternativeRight.com. Amidst crude language, the article suggested that the West had a problem: even though we are told that the Holocaust is the universal image to associate with suffering and oppression, it is also too hopelessly Jewish to connect with non-Jews.

This was, perhaps, a peculiar article for Maddow to pick up on, but it does something that fascist ideologies often try to do: it takes a real debate and reframes it through a fascist lens. The question of the ubiquity of Holocaust narratives is one that drives conversations on how to interpret far-right threats, particularly now that we see a global rise of national populism. When congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio Cortez visited the migrant detention centers housed along the United States’ southern border, she referred to them as concentration camps. This brought a round of denunciations from various sectors of the Jewish community and the political right. How could she compare the incomparable? But what that criticism suggests is that the Jewish experience in the twentieth century is so particular to Jews themselves that no other people, no other situation, can be compared. If it is the case that the Holocaust is so distinct that nothing can relate to it, then what do we have to learn from it?

This debate is part of what drives Joshua Cohen’s fabulous new book, British Antifascism and the Holocaust, 1945-79, which looks at how antifascist activists mobilized the memory of the Holocaust in their movement messaging. The Holocaust still looms over us as the most prescient example of fascism’s consequences, and antifascists continue to debate how to reference this history when building a rhetorical strategy meant as galvanizing public support for fighting the far-right. As Cohen outlines, the mobilization of Holocaust messaging was not a linear process, and as we got further away from the event itself, and as antifascism became less Jewish-specific, the Holocaust played an increasing role in antifascist messaging.

Subscribe to the newsletter

Cohen’s book is part of the Fascism and Far Right Series at Routledge, which, under the effective tutelage of Graham Macklin, Nigel Copsey, and Craig Fowlie, has become perhaps the most influential contemporary scholarship on antifascism. Cohen provides something new and compelling that has not already been addressed by Copsey, David Renton, and other authors in this series. Cohen focuses on the relationship between the Holocaust and antifascist consciousness, and addresses a number of related concepts, such as the history of Jewish antifascism, its relationship with Jewish civic organizations and Zionism, and the tactical debates between the socialist and Labour left in Britain. Cohen’s angle on this history expands our understanding of this history in incredibly novel ways.

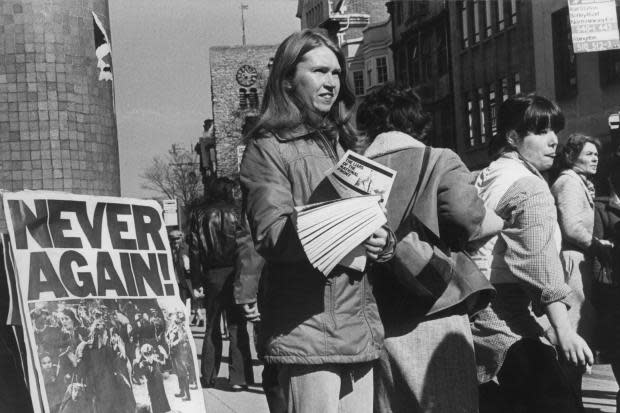

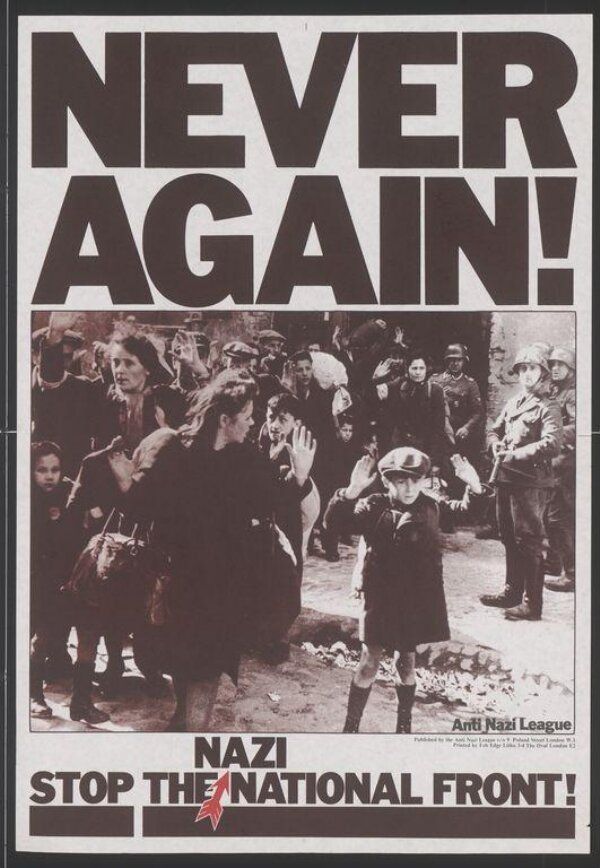

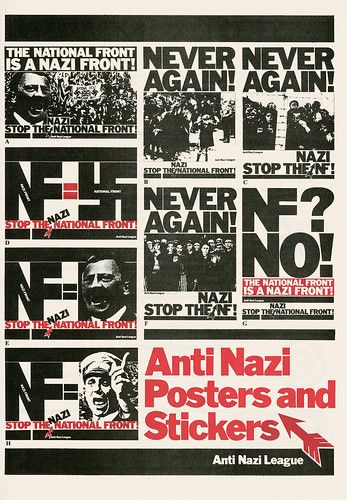

Cohen unpacks several key issues that retain their relevance in political debates today. One is the conflict between the Jewish specificity of the Holocaust and its ability for non-Jews to relate, but also the centrality of antisemitism in understanding fascism. By the mid-1960s, the far-right began focusing less explicitly on Jews and turned its attention towards non-white immigrants from former British colonies. Antisemitism became coded, and at a time when Ashkenazi politics became more conservative across the Anglosphere, open questions remained about what role a narrative tied so explicitly to Jewish experiences, and employed in Zionist rhetoric, would have for an antifascist left that sided with Palestinians. Cohen shows that the trajectory was towards more Holocaust memorialization rather than less. When the Holocaust was a more recent memory, and when Jews were more explicitly a part of antifascism as Jews, the Holocaust was both less referenced and more relativized. It wasn’t until a few decades had past and Jewish identity was less central in antifascist organizing that the Holocaust emerged as a more prevalent reference point. This development marked the growth of the Anti-Nazi League (ANL) and Rock Against Racism in their fights against the neo-fascist National Front. Cohen notes that part of this was the ANL’s strategy for defeating the Front, which was to make it very clear to the public that these were not patriotic conservatives, but fascists of the same variety Britain fought in the war. Holocaust narratives explained why the Front needed to be defeated, and the Front’s treatment of the Holocaust, particularly Holocaust Denial, helped reveal the Front’s Nazi politics.

Cohen’s history surveys the organizing of groups like the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), elucidating both the development the left made on these issues and its historic failure to understand the full scope of the Holocaust and its related antisemitism. Cohen’s concision is admirable, the work is simultaneously detailed and condensed, thoughtful and direct. Cohen’s core point of analysis embeds with it so many related issues, such as Jewish identity, Jewish politics, the relationship of the left to mainstream political memory, and many more avenues. This may be the biggest sign of the book’s achievement, that Cohen’s point of reference creates dynamic position from which to examine the conflicting political issues that surround the core debate.

Subscribe to the newsletter

British Antifascism and the Holocaust, 1945-79 is amongst the best recent books on antifascism, and if any criticism can be leveled it is simply a result of the narrowness of the book’s scope. The final chapter on the Anti-Nazi League digs into the criticisms leveled at the ANL’s strategy from within the left, and Cohen employs primary sources in ways surprisingly novel for a period that has been well covered in the literature. But what would have been useful is hearing more from dissident parts of the left, such as from anarchists, or hearing about interactions with post-ANL projects and more discussion of the ANL’s relationship with the non-British left. We could have also learned more about the interesting dynamics that played out between the Board of Deputies of British Jews and the Jewish antifascists, or the Zionist establishment and these radical dissidents. What these Jewish militants offer is essentially an alternative vision of Jewish safety to the model of centrism and nationalism offered by the Jewish civic establishment. These avenues, however, are possibly too far afield from the book’s scope; that these questions linger is as clear a sign as any that the book has made an impression. Cohen has grasped at some unexamined bits of our history, drawing the reader to really inquire as to these events’ meaning, and he has pointed to where another generation of scholars can make their contributions.

It’s hard to see this book as separate from the recent wave of interest in Jewish antifascism. We’ve seen the growth of groups like Jews Against White Nationalism and Outlive Them, organizations that have taken on the call of Jewish safety in ways directly at odds with the Jewish communal consensus. While Jewish civic life has been largely governed by moderate political tendencies and hinges on the idea that Israel remains a source of safety, the explosion of antifascist consciousness of the past decade, and the resurgence of an explicitly Jewish left, has repositioned antifascism as an alternative model of safety. Cohen’s history places antifascism as not just occurring in proximity to Jews but emerging out of a distinctly Jewish experience of community self-defense, occurring both before and after the Holocaust. Cohen’s book seems to be part of an emerging canon, including Max Kaiser’s Jewish Antifascism and the False Promise of Settler Colonialism (2022), Cindy Milstein’s edited volume, There Is Nothing So Whole as a Broken Heart (2021), , Daniel Sonabend’s We Fight Fascists (2019), or Jewish-specific works embedded in larger studies of antifascism, like Benjamin Case’s recent essay “Antisemitism and the Origins of Totalitarianism'' in the volume I recently edited, No Pasaran: Antifascist Dispatches from a World in Crisis (2022). While we have often been told that the “Jews moved right,” Jewish antifascism puts Jews back into alignment with other oppressed people by highlighting a most obvious form of marginalization, that coming from the far-right. Just as Cohen discusses how the antifascist movement wrestled to understand Jewish history and antisemitism, the same thing is happening in the modern left with antifascists fighting to understood more fully antisemitism and Jewish experiences within activist spaces. This is part of where Cohen’s work will find relevance, as a history that not only informs political debates today, but also holds up a mirror to our current frictions.

British Antifascism and the Holocaust, 1945-79 seems to have begun as Cohen’s doctoral dissertation, then expanded. It’s fair to say this is a stellar debut for an emerging scholar, one who has breathed incredible life into a well-considered topic. It is a good sign for what his career has in store for us. Cohen places antifascism within the academic traditions of Holocaust and Genocide Studies, recasts this social movement as an essential protectorate against the mass violence of unhinged nationalism, and highlights its importance for both Jews and Gentiles in a shared struggle for a different future. The best we can do is to pick up where Cohen left off, not only extending his analysis in the 1980s and beyond, but by asking dynamic questions about the role of historical memory in the decisions we make today in the effort to stave off the worst instincts of the far-right.

I would also recommend that if you are interested in learning more about the Anti-Nazi League, the 43 Group, the 62 Group, and other movements featured in this book, pick up David Renton's Never Again: Rock Against Racism and the Anti-Nazi League 1976-1982 and Nigel Copsey's Antifascism in Britain.