Jewish Anti-Zionism is at the Bookstore This Year

While much of the media has framed the massive surge of Palestine-solidarity protests hitting American streets and the lawns of major universities as categorical antisemitism, there is one fact that calls this analysis into question: these protests are pretty Jewish. Whether it was giant menorah blocking city bridges or liberation seders held at the college encampments, Jews are disproportionately represented in the ranks of American Palestine solidarity activists. This is because despite how much consensus support for Israel organizations like the American Jewish Committee assumes of Jews, the reality is that there is a steady, growing, and historically consistent tradition of Jewish anti-Zionism. Considered verboten by many mainstream Jewish organizations, there have been Jewish opponents to the project of creating a Jewish state in historic Palestine since decades before that state’s arrival, and many of those objections evolved into adamant resistance as the consequences of Israel’s occupation became more obvious.

With the shifts happening in Jewish politics on Israel, a number of scholars, authors, activists, and rabbis have set out to document the changing reality of American Jewish life by producing a slate of new books centered on the particularly Jewish tradition of anti-Zionism. After we saw offerings like Shaul Magid’s The Necessity of Exile in 2023, 2024 has already seen five major contributions to this, each of which is offering something distinct and important as they break ground in covering a movement so often tarnished as a contradiction.

2024 has seen the release of two scholarly books in particular that, while presenting a similar framing for how to look at the history of Jewish anti-Zionism, thankfully largely cover different areas (and what overlap they have is interesting). Geoffrey Levin’s book, Our Palestine Question: Israel and American Jewish Dissent, 1948-1978, looks specifically at the years between Israel’s formation in 1948 and 1978, zooming in on a particular segment of the Jewish community’s dissent from Zionism. Levin’s book really does start with Israel’s formation, so the question is not just of Zionism as a political outlook or trajectory, but more about how the Palestine refugee crisis (as many titled it in the early years after the Nakba, the forced displacement of around 750,000 Palestinians during Israel’s formation) are to be handled in Jewish spaces. We start with the story of Don Peretz, a former Zionist whose trajectory to concern over the treatment and erasure of Palestinians is one that has become familiar for many on the American Jewish left. Working for the Quaker organization the American Friends Service Committee, he saw the immediate aftermath of the expulsions as early as 1949, and some of the displacements he witnessed firsthand. Peretz moved on to the American Jewish Committee, of all places, where he produced pamphlets and where pressure mounted from Israeli diplomats to fire him. Levin goes on to talk about a number of key figures in the evolving criticism of Israel, from Yiddish journalists to communal leaders, and his study culminates in a fascinating chapter on the Jewish New Left group Breira.

Subscribe to the newsletter

While still a Zionist organization, Breira caused controversy for setting up diplomatic meetings with the PLO in the 1970s and faced subsequent backlash from mainstream Jewish organizations. This may be the most instructive of all the chapters in the book since it reflects many of the experiences that Jewish progressive activists have had in recent months as demanding a ceasefire in Israel-Palestine has been enough to label longtime Jewish community members as heretics. Breira is also part of a lineage that has led up to more contemporary Jewish-led Palestine solidarity groups such as IfNotNow and Jewish Voice for Peace (more on them later), but the interesting difference is that Breira always noted itself a, however critical, supporter of Israel. There has been a sharp decline in the “radical Zionist” position that was once common in the Jewish New Left, likely as Israel’s occupation in the West Bank surpassed the half-century point and the Israeli Right has become the entrenched ruler of the country. Levin’s history points to a number of internal documents and never before released evidence and paints a clear picture of the efforts that were made to suppress dissident Jewish voices who were trying to raise the alarm about a humanitarian crisis that was only going to get worse.

The second book covering a similar history is Marjorie Taylor Feld’s The Threshold of Dissent: A History of American Critics of Israel, which starts earlier than Levin’s book with anti-Zionist voices that emerged before the foundation of the State of Israel. This begins with the American Council for Judaism, a Reform movement project of rabbis who opposed the Zionist project since they believed it would undermine their assimilationist claims to be “Americans of the Jewish faith.” This is a largely lost tradition from the Reform Movement that denied Jewish peoplehood and pushed more to have Judaism represented on the American model of private belief. Most of the Jewish community has moved past this opinion, including the Jewish Left, but it was a key part of the objections that American Jews expressed to the Zionist project early on. While the Council’s leaders started with this core objection to the Zionist assumptions about Jewish identity, they eventually turned towards concerns over the treatment of Palestinians and you can see that, even before the foundation of Israel, there was widespread consciousness that creating a Jewish-specific state in historic Palestine was going to be unjust for the Indigenous people who had been living there for centuries.

Feld also chronicles some of the key critical journalists and scholars, and both Levin and Feld have a chapter on Yiddish journalist William Zukerman, the creator of the Jewish Newsletter and a figure whose career was seriously impeded when he spoke out against Israel’s conduct. Feld then zips forward into the New Left to see how anti-colonial Jewish movements talked about Israel before moving into a chapter on New Jewish Agenda (NJA), itself an evolution on the politics of Breira and other groups at the time. While not an anti-Zionist group per se, NJA was a significant part of the evolution of anti-Occupation organizing among leftist American Jews, as well as a place where Jewish activists fought homophobia, sexism, and international problems, such as the treatment of Jews in Argentina. Despite NJA’s firm commitment to the future of Jewish life both in the US and in Israel-Palestine, they still received little support from groups like the Anti-Defamation League, which was inherently suspicious of NJA’s civil rights work and who thought their criticisms of Israel crossed the line. This history also feels eerily familiar to those working on related issues today as the ADL increasingly causes consternation amongst progressives who feel like its stated mission to stamp out hate is being impeded by its aggressive role as an advocate for Israel. We even see flashpoint stories in the chapter like when three rabbis held a beit din (Jewish religious panel) to excommunicate some NJA members in 1982 (this famously included linguist Noam Chomsky). Some of those who attacked Breira as traitors to the Jews in the 1970s said the same about NJA in the 1980s. They haven’t been any less silent today.

Subscribe to the newsletter

Oren Kroll-Zeldin, who serves as Assistant Director of the Swig Program in Jewish Studies and Social Justice at the University of San Francisco, took a slightly different approach for his book by not only bringing his research into the present, but by putting his own activism at the center of the narrative. Kroll-Zeldin’s book chronicles Jewish-led Palestine solidarity organizations, including chapters covering Jewish Voice for Peace, IfNotNow, activists “walking off” Birthright trips in Israel, the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement, and debates both inside and outside of Jewish communal institutions. A big portion of his book, which is called Un-Settled: American Jews and the Movement for Justice in Palestine, focuses on his own work in what’s called “co-resistance,” whereby Jews and Palestinians participate in collaborative activist work in Israel-Palestine. His work was specifically with the Center for Jewish Non-Violence, which focuses on non-violent civil disobedience, such as blocking IDF soldiers and vehicles that are trying to do things like demolish Palestinian homes or uproot olive trees. Kroll-Zeldin takes an ethnographic approach to the study, alternating between personal experiences and interviews with other activists, and builds this on top of an intricate foundation of research and background. What we end up with is more than just a document about the state of Jewish-led movements, it is also a personal narrative that many Jewish leader may relate to as they find themselves out of step with the direction of the organizations they serve in.

It’s also worth noting the complex position this puts Kroll-Zeldin in, not just as an associate professor (a position that still awaits a tenure review), but as one who leads a Jewish Studies program. These programs are often a place whereby Jewish organizations help to create continuity with young Jews and not insignificant pieces of Jewish education take place so that a next generation of Jews can participate fully in synagogue and communal life. With donors and grants at stake, not to mention hiring and curriculum decisions, opinions critical of Israel are rarely voiced in these spaces. So for Kroll-Zeldin to not just write this book, but to put himself emphatically at the center, is an uncommon kind of bravery, one that shows a sea change in what is acceptable in a “Jewish space” at American universities. This is likely to get only more complicated as the current hysteria over campus protests continues, and even moderate opinions are denounced as grounds for dismissal.

While Kroll-Zeldin’s book puts his activism front and center, Solidarity is the Political Version of Love: Lessons from Jewish Anti-Zionist Organizing is an open, loving, and honest look back on the formative years of Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP), the largest Jewish anti-Zionist organization in the country. The book, published by the socialist press Haymarket Books and named after a quote from influential Jewish feminist Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz, is written by Rebecca Viokomerson and Rabbi Alissa Wise, who were in leadership at JVP as it evolved from a small, mostly Bay Area phenomenon, to a nearly 25,000-member organization with a slate of staff. Instead of simply recounting history or unpacking the Israel-Palestinian conflict, Vilkomerson and Wise jump right into the practical lessons they learned from doing the work every day. This is an organizer’s book, one that is meant to inspire real world action by parsing out what worked, what didn’t, and what must be done differently next time. This focuses on what they frame as the “both, and'' approach, acknowledging contradictions and limitations while working to reconcile a positive solution. They talk about issues that occurred internal to the organization, such as the acknowledgement that for years JVP had an almost exclusively white leadership, and the steps the organization made to chart a different future. These tense organizational movements led to the creation of the JVP Mizrahi, Sephardi, Jews of Color caucus, a major development not just for the Palestine solidarity movement but for evolving the Jewish left as a whole.

Subscribe to the newsletter

Wise and Vilkomerson discuss how the increased presence of Jewish ritual and tradition caused some friction with some of the older members, who represented a more thoroughly secular form of Jewish political identity (a tension that is playing out across the Jewish left). For many Jews, JVP is a chance to not just engage in activism to stop Israel’s apartheid system, but also a chance to reclaim Jewish identity and spirituality apart from Zionism. This is where “yes, and” comes back into play, acknowledging that a large organization has different personalities, approaches, visions, and agreements, and building a project on solidarity is no less difficult than founding a relationship on love. This book stands out from the pack in that the authors intend for the text to be brought back into organizing spaces, for people to try out the ideas implied within and even to disagree with the author’s conclusions: this is part of the work they have been doing for decades, not just a narrative compendium of memories. This is a perfect example of the political strategy of book writing, where the hope is to help shift action in the real world far beyond simply changing minds.

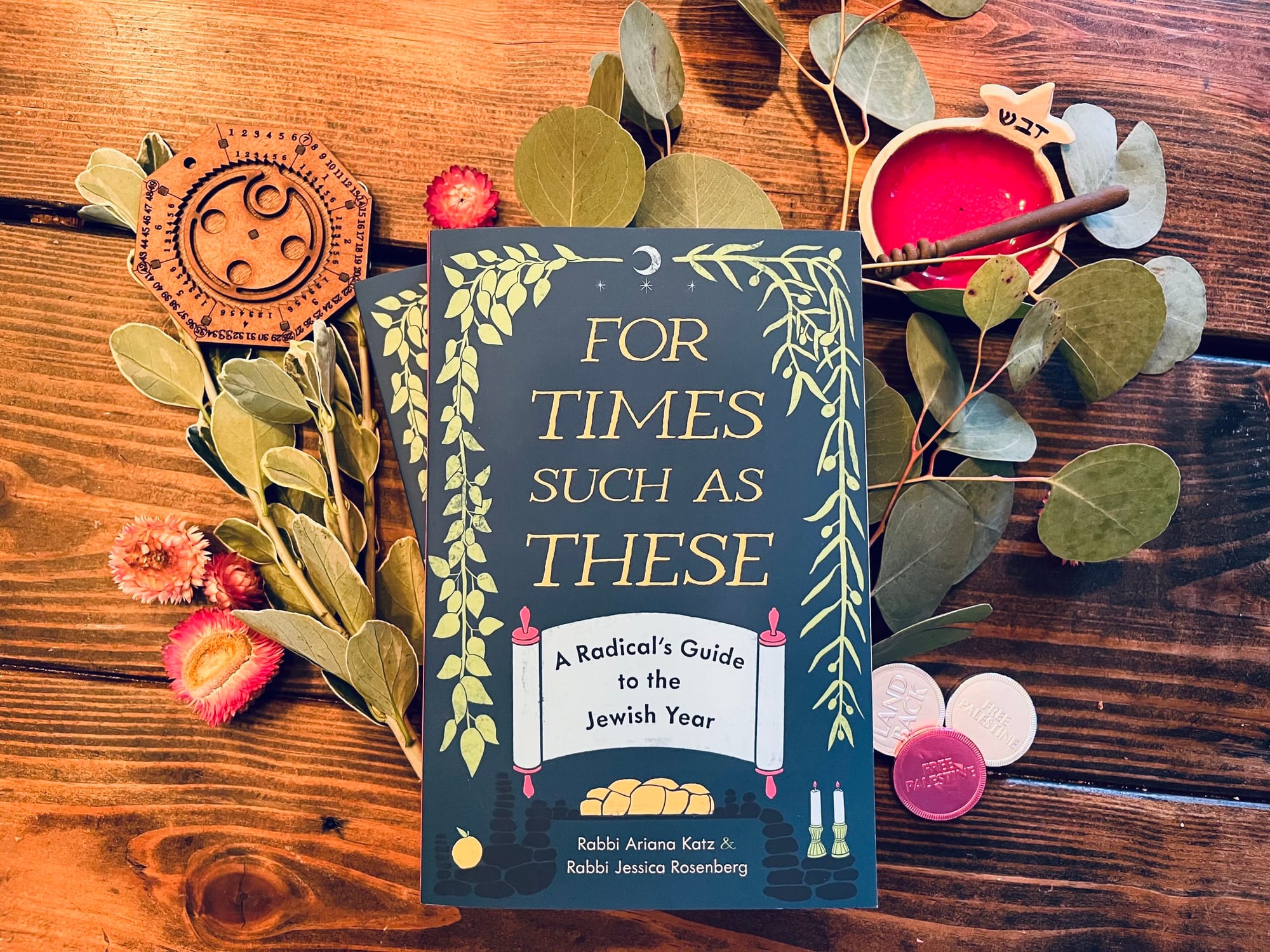

If JVP’s work is, in part, creating a Jewish community outside of Zionism, then two members of their Rabbinical Council have created one of the most important contributions to that effort in years with their book, For Times Such as These: A Radical’s Guide to the Jewish Year. Rabbi Jessica Rosenberg, who is active in the Radical Jewish Calendar project and Matir Asurim: Jewish Care Network for Incarcerated People, and Rabbi Ariana Katz, who leads synagogue Hinenu in Baltimore, have created a new book tracking Judaism’s year-cycle with a particular eye towards radical re-interpretations of tradition and with an intentional step away from Jewish associations with Zionism. Both rabbis are graduates of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, now the site of perhaps the largest presence of anti-Zionist rabbis in the country, and the influence of that movement looms heavily as they discuss Judaism as a “spiritual technology” that can do things such as help us process grief or tap into historical lessons from our ancestors. As the country’s small “major movement” of Judaism, Reconstructionism is often left out of conversations in mainstream Jewish life, but as it becomes a primary area for the Jewish radical left it may be that it will prove to be amongst the most influential in creating the next generation of active Jewish life.

While the book is consistent in its anti-Zionist positions, it does not weigh too heavily on the text itself, and that is by design: they are building Jewish spirituality past Zionism, not just in response to it. What you end up with is a politically radical, queer, inventive, and incredibly intimate guide for how to claim holidays, shabbat, halakha, text, history, tefillah, and all aspects of an involved Jewish year and to make them your own. The real strength of the book is that its distinct vision of how to apply the Jewish spiritual mission is powerful enough to attract people whose politics on the question of Israel come second, making a new entry point for the debate and helping to build up a more complex repertoire for those thinking about what Judaism can become this century. For Times Such as These should immediately become canon for radical Jews, and the growing number of them (us) who are turning to Jewish spirituality to find a revolutionary direction past the limits of mainstream American life.

What binds all of these books together is that they want to open up our discussions not just about the politics of one of the most important disputes in modern history, but to validate the Jewish experience of dissent. Much of mainstream Jewish life, and literature, assumes that anti-Zionist Jews are within the margin of error: an insignificant, irrelevant, and unrepresentative sample of American Jews. But this is largely a modern construct, one built by what Peter Beinart calls the “American Jewish Establishment,” whose social agenda is not always in line with the Jewish communities it loudly claims to represent. Instead, there is a sizable, and growing, contingent of Jews who are sticking with their Jewish identity and not only challenging the pro-Israel consensus, but doing so from within Judaism. 2024 has seen a wave of these books, but this output is likely to pale in comparison to what will be released ten to fifteen years down the line as researchers and writers try to document how wide this divide has become over even the last year. This is a centerpiece of the Jewish story in the twenty-first century, and no amount of erasure or invisibilization from political pundits or non-profit CEOs can change that.