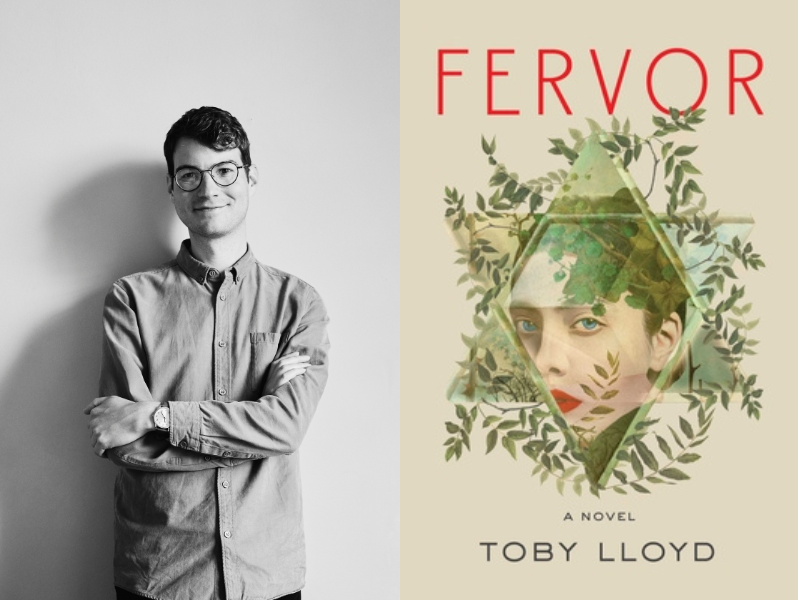

Portrait of a Jewish Family

Toby Lloyd's debut may be the best, and more heart wrenching, Jewish book this decade.

An interesting thing happens when you light Shabbat candles. If you linger until the sunlight dims, and you set aside work, phones, and the comforts of the modern world, a shift in time and space takes place after the prayer is said. You are transported to somewhere else, where the rules are different and the pressure of an increasingly disconnected and volatile life evaporates. The world cannot find you, if you don’t let it. In doing so we confirm one of the timeless truths of ritual and tradition, that they are a story and metaphor using spiritual language for experiences that are effectively material. And we finally discover that the modern conception we have of reality is not just insufficient in terms of its emotional lyricism, but that, sometimes, our antiquated mythologies know more about the human experience than all the descriptive might of modern literature.

Toby Lloyd’s unparalleled first novel Fervor lives in the space between Biblical literalism and the messiness of human lives and does something nearly impossible: it allows two competing interpretations to remain true. Fervor has been marketed largely as a Jewish horror novel, a sub-genre that hardly even exists in the contemporary literature market, yet it fits more comfortably in the world of family dramas that watch relationships fracture and break without the opportunity of healing. The story follows the Rosenthal family, a father who grew up frum (Orthodox) and a mother who became baalei teshuva (a secular Jew who becomes religious) after she realizes that there has always been a loving presence watching her as she makes moral decision after moral decision. The two have a family and yet Hannah, the mother, remains unsatisfied in her career as a writer. She decides to make an unpopular decision: she will write a memoir about her husband’s father, a Holocaust survivor who was forced to participate in the inner workings of the concentration camp he barely survived. After Hannah tells Yosef, the grandfather, that she intends to write the memoir whether he likes or not, he becomes a melancholic realist as he deals with the fact that his secrets will not remain as such. “And the whole world will know what I did?” he asks Hannah, who responds, “Anyone who reads will understand,” she replies. “You think people are better than they are,” he says, and we wonder if, after meeting Hannah, he is correct.

The story is largely told by Kate, Hannah’s son Tovyah’s friend (who could possibly have been more) as she encounters not just the family, but Jewish life as a compelling idea. She arrives second hand, having one Jewish parent and little history in tradition (a background I know intimately). So when she comes to hear a Jewish author speak at a meeting arranged by hasidim, when she is asked if she is Jewish she replies with a pensive “sort of.” This sends the frum man she is speaking to into a fit of laughter. Sort of. Who has ever heard of such an absurd thing?

Subscribe to the newsletter

We hear more about the family, particularly Hannah’s daughter Elsie who disappears briefly as a teenager only to return somewhat different, changed and dysfunctional to those who demand a certain life from her. After years of substance abuse and violent outrages, Hannah finally figures out what is wrong: Elsie has been possessed by a demon after recklessly reading Zohar, a book of kabbalistic Jewish mysticism. The book centers around her angry children, particularly Tovyah, and this only becomes more severe with the release of her second memoir outlining her pet theories about her child’s fate as a type of Hebraic changeling. All of this circles around the reality of unpopular Jewishness, particularly Hannah’s constant op-eds in defense of Israel and directing venom at the Palestinian liberation movement.

While the tepid pacing of the first few chapters takes a little while to adapt to, it quickly becomes a quixotic take on the gap between Biblical literalism and reality. Hannah and her husband look to Torah/Talmud to answer painful questions, which provide as much of an answer as any of our characters are going to get, yet this still leads to an utter rejection by Tovyah in what he sees as his mother’s selfish immorality. The text quickens, introducing character layers in a way that matches the mythological pairing offered by Hannah’s comparison. This escalates as the book goes on to the point that it becomes almost an assault on the reader in the final pages, when the fragments of detail scattered like shards across the narrative are pieced together into a caustic bludgeon at the end. This is not a book that lives in its subtleties, but, as anyone who remembers reading parsha in Hebrew school, neither is the Bible. Fervor feeds on the fact that myth may end up as suitable explanation for human crisis as any other, than accusations of witchcraft and the experience of familial bipolar disorder may live in the same emotional reality. People do, in fact, disappear, they become someone unfamiliar, they feel possessed by something otherworldly, just as we are when our grief becomes so profound that it feels implanted by some alien force. Because of this, Lloyd takes the philosophic lessons of Jewish mysticism seriously, perhaps even more seriously than his characters in that he lets us see that each human story can be captured, to a degree, by the fables we’ve told for centuries. These stories are true, or at least as true as any story.

Fervor is a Jewish book, perhaps the best Jewish book of the decade, one that never abandons its primary civilizational inspiration. There is a comfort, and a great deal of respect for the reader, in the way that Lloyd never assumes we need a religious studies lesson to follow his thinking, but instead effortlessly takes us through antiquated texts and esoteric allusions in a way that somehow captures the sublime energy of each. The ability that Lloyd shows here is utterly unparalleled, and while he will be (fairly) compared to popular novelists like Dara Horn, he delves deeper into the roots of Jewish thought than I ever imagined possible in an accessible piece of fiction.

Fervor starts as heartbreak and ends as utter devastation, but only in a way that proves that Hannah was right: someone has been watching. “And I knew then, with absolute certainty, that there is a God who created the universe, a fog at the centre of the flame,” Kate describes, mirroring Hannah’s revelations decades earlier and experiencing comfort in a reality that provides neither solace nor salvation. Not necessarily.

Subscribe to the newsletter

The symmetrical imagery Lloyd relies on allows for Fervor to appear as though it is itself part of the logical Jewish canon, beginning with Torah and continuing through the variously evolving periods of Jewish society all the way to the novels we use to make sense of our history. Our tales do not exist in a literal realm free from magic and mystery, but in the same world Moses claimed to document. Our stories exist in the same continuum, where we attempt to decode their meaning through a collective effort of memory. It’s unclear what the Rosenthals learned from their years in textual study, or what lessons we should gain from reading their lives, but Fervor remains a reminder that there are perennial images that will always appear when we try to parse out the utter baffling experience of being alive. Once you tear your own hair out you may finally understand while others have, as well. As some of our periphery denounce Hannah’s second book, a narrative work that pillories her own daughter, one person references Oscar Wilde’s famous line that “there is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book.” Fervor is a moral book. Or, at least it hopes that such a thing is possible.

Fervor is a tour de force, only made more astounding by its position as Lloyd’s debut. Few books establish a balance between its work as a complex literary masterpiece and a sustained series of gut punches, which never collapses into petty gossip or manipulative cliches that so easily could have been its crutch. The discussions of antisemitism are real and nuanced, playing out the conflicting dynamic that is true in conversations about anti-Jewish ideas at a time when Israel is the object of so much justifiable anger. I expect that Fervor will be returned to over the years, that after we see the full breadth of Lloyd’s career it will be put into its proper context as the prophetic work that it was. And, by watching the Rosenthals from a distance, maybe we will learn what it means to live a life that was never alone.