Reading Horror, Genre, and Politics At the Beginning of 2025

A look at the first quarter of 2025, what we've read, the classics we are rediscovering, and the great books releasing this year.

So I am doing this a little differently this time and instead reviewing some of the horror books from the first quarter of this year, ranging from 2025 new releases all the way to some horror classics I’ve never had the chance to read before. Over 2025 I hope to plumb the depths a bit, get into older and international books in translation. In 2024 I focused specifically on books that came out that year and, while there were some fantastic reads, this is not exactly the best way to hit the cream of the crop. An artificial, temporal boundary doesn’t ensure the “best,” or even preferences, but instead simply offers a limited pool with little attention to quality. So I’ll be interested to discover gems I’ve missed, both recent and in decades past, as well as try to create a series of Jewish horror, something that is remarkably almost completely missing from the canon.

In an effort to dive into anything broadly understood as “Jewish Horror,” a phenomenon much more scarce than one might expect, I am reading the novels by Ira Levin, who, while perhaps more of a “thriller” author, is often named as an important Jewish horror scribe. The most Jewish of his horror-tinged books is The Boys From Brazil, which was also made into an Academy Award nominated 1978 film that looks at a bizarre plot hatched by former Nazi agents now living in South America. The book vaguely constructs a Elie Weisel figure who hunts Nazis across borders, living a life of austerity with his sister so he can hold German officers accountable for their horrors. The book is fun, but, by way of parody and pulp repetition, seems incredibly familiar, which is another way to say it is terminally dated. The underlying plot will cause a bit of an eye roll, but the pacing is so masterfully laid out and the post-Holocaust fear of the time in which it was written so palpable, particularly as expressed through the eyes of Jewish characters, that it's an easy book to enjoy. Most interesting is the Meir Kahane inspired figure, who Lieberman (the Weisel proxy) comes to final conflict with, but who also displays a kind of grudging respect. The experience of the Holocaust and the victory of Zionist historiography has created an unspoken ubiquity of deference to those who used violence in the cause of Jewish defense, even when they take on Kahane’s underlying reactionary perspective. This was visible particularly during the Jewish Defense League (JDL) when more moderate Jewish voices, while condemning the violence and racism, still offered quiet admiration. The Boys in Brazil seems to understand this guarded affection: we saw what happens if we don’t fight back.

But The Boys in Brazil still feels older than his earlier, 1967 classic Rosemary’s Baby, which is timeless. Roman Polanski’s film is remembered as a key icon of the feminist horror moment, but the book itself probably cemented that title more effectively. This was my first time reading the book, which I always understood as a parable about abortion, yet it’s themes are more expansively about bodily autonomy, particularly the lasting consequences of sexual assault (as well as what it means to be a “secular Catholic,” which Levin seems to use as his own proxy for “secular Jew”). In an essay by Vanessa Maki for Interstellar Flight Magazine (which is more about the film) points out that the story is about the profound powerlessness that our main character finds at every moment. The sex is violently imposed on her, her medical decisions are stripped from her, she is scarcely even permitted to leave her home, and her parentage is denied, until the final pages where she chooses to conform, in a way, to the dictates of her captors. The book is remarkable in how easy and enticing it is, how every moment feels contemporary and genuinely frightening in a way that religious horror often cannot maintain years after its publication.

This is perhaps the lasting mechanism of Levin’s craft, his economy of words, his simple escalations, the hints his characters leave traces of that reveal who they truly are. This is what Chuck Palahniuk pointed out in a 2007 essay on Levin (he also writes the introduction to Rosemary's Baby) that, while with "transgressive fiction" the politics and philosophy of the author is basically shouted from the rooftops, Levin conceals the more practical implications of his perspective inside the emotional reality of the story with such skill that he could be consider a master persuader. "What's creepy is, these are issues the American public is years away from confronting, bu in each one – in each book– you [Levin] ready us for a battle you seem to see coming," writes Palahniuk. "The fable lifts an issue free from its specific time and makes it important to people for years to come. The metaphor even becomes the issue, injecting it with humor, and giving people a new freedom to laugh at what had scared them before." Hopefully, no one experiences what Rosemary did, they will see the signs, they will coordinate an attack, they will defend themselves. And, regardless, clearly the only solution is that women should have complete bodily autonomy. We don't even need to say it because the experience of sharing this story with Rosemary implants this idea deep in the emotional register of the reader.

Subscribe to the newsletter

As part of looking backward I finally picked up a book that has been on my list for years since it remains a favorite among the online world of Reddit commentators and BookTok recommendations. Dathan Auerbach’s Penpal began as a series of posts on R/NoSleep, which eventually was collected into a novel format and led as an example for the later discovery of Reddit authors. It is structured as a series of childhood memories from a now adult man recounting, with hindsight that is only shared slowly over the course of the text, that his childhood was defined by a threatening stalker. Auerbach’s second book, Bad Man, felt remarkably similar since both of them are about the unimaginable grief of losing a young relative, the way some wounds don’t heal and instead can just stretch to cave in your entire life. Penpal is brilliant, partially because of a pacing that will make readers race through the text despite most of the horror being quiet, small, and seemingly insignificant until the final chapters. It also shows the great emotive possibilities of true genre fiction since Auerbach is not trying to work outside the confines of the genre and instead uses its tropes as signposts to work his tragedy into. This is why grief is such a persistent motif in American horror, why memory, loss, and heartbreak make for such viscous frights.

Slightly less successful is KC Jones’ new novel White Line Fever, a book that shows the profound difference that underlying themes can offer when compared to Penpal. Equally quiet and quick written, White Line Fever tells a haunted highway story that frankly lacks much of a punch or really anything to say beyond the obvious shocks on the page. This is Jones second novel after Black Tide, which likely would not have stood out without the Lovecraftian characterizations that sat atop what was essentially a survival story. White Line Fever shows Jones as an adequate horror author, there is nothing here to indicate they are anything other than adept at genre storytelling, but with a crowded market it’s hard to recommend this with any particular fervour.

In an effort to pick up even more of the classics of American literary horror, I began reading the Penguin Classics reissue of Thomas Liggotti’s Songs of a Dead Dreamer and Grimscribe, a compendium combining these first two landmark collections. Ligotti is less known than he should be (except as the inspiration for Rushton Cole in the first season of True Detective), but it is fair to acknowledge that his output is not for every reader. A deep cosmic and existential strain runs through his work, though some stories become so unmoored from reality and so caught in his tangle of arcane language that it can be a challenge to follow. There are horror stories that inject frightening elements into the story space they have created, and therefore depend on some common language that the reader understands so they can enter this new world. There is other horror that plays more with emotion and aesthetics, whereby the plot is secondary, and that is where much of the Ligotti prose ends up, which may strain the more story-bound reader. That said, when they hit they do so with aplomb, particularly his open Lovecraftian work with the Cthulhu mythos. Ligotti is perhaps best when he at least maintains some connection to literary convention, otherwise you get lost in the depths of his ruminating psyche. This is a long book, and where I would recommend those looking for a deeply pessimistic, nihilistic, and haunting cosmological terror to break apart any sense of hope they have for the human race (Ligottis is sure that a plot is already against us).

On the theme of classics I also jumped into the first three volumes of Clive Barker’s Books of Blood, which is what launched him into the horror world. Barker’s celebrity feels of a different generation, perhaps because of the style of his filmmaking or even the brazeness of sexual violence that is handled with more delicacy by younger hands. But his first few books maintain the love for the genre that shifted in his later canon: he has become more of a fantasy writer than a horror hardliner. The Books of Blood are a collection of short stories, which is by definition hit and miss, but there are some fantastic classics here: “Midnight Murder Train” (which has a decent film adaptation starring Bradley Cooper), the prep-school set “Pig Blood Blues,” the fairy tale “The Skins of the Fathers,” “Dread,” “Human Remains,” and, the best of the lot, “Scape-Goats,” something that reveals my preference for folk horror.

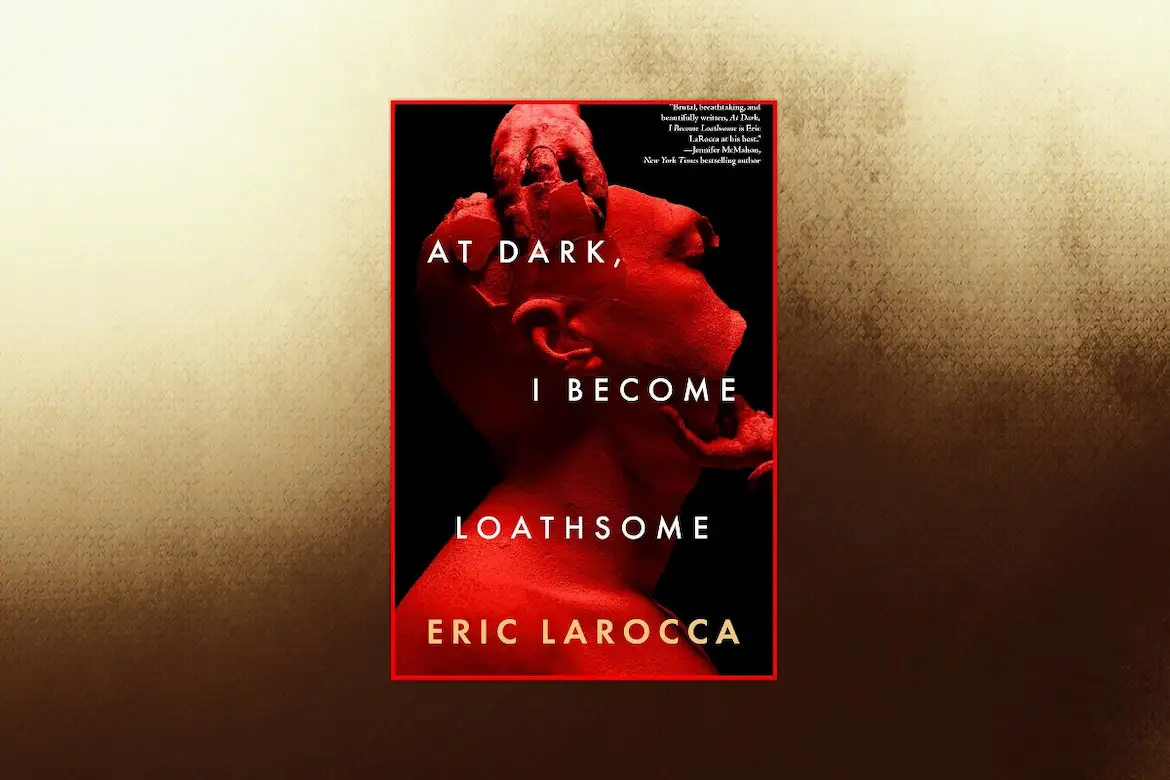

What’s most obvious about these stories is Barker’s influence on modern horror, particularly the more macabre parts of this. This was especially visible since I had just read Eric LaRocca’s new book, At Dark, I Become Loathsome, the natural evolution of the Barkerian influence on the genre. The book is dividing people, particularly when the reader arrives at some of the “stories within a story” that push on the limits of decency and can become reasonably upsetting. This is a reminder of why books can deserve to have “trigger warnings,” which LaRocca sometimes does. If you recently had a relative die of cancer you might want to wait a year or two to enjoy some fabulous novels with cancer plots until you feel fully able to grasp it. But what At Dark, I Become Loathsome does so well is drops us into an accelerating storytelling machine that pushes us to keep reading, to dig up relatable parts of ourselves we usually hide, and to admit our capacity to consume one another. This is a stand out already this year, particularly on the darker side of mainstream horror.

Subscribe to the newsletter

Part of why I read so much horror is that I like to crest along the edges of the genre to see exactly what different voices mean when they claim the mantle. I am a genre reader, which means I like the mediocre examples of horror as my baseline. But what horror is capable of is designated by people who create works that straddle the genre edges, perhaps they don’t consider themselves genre writers, and maybe genre fans do not include their books on the horror shelf. So far, Rivers Solomon’s Model Home (2024) is the best example of this I’ve read in 2025, and probably the best horror novel entirely, which is an attempt to redefine the haunted house genre. Two parents die, or perhaps were killed, and their estranged children return to their overwhelmingly white Texas suburb to deal with the home that terrorized their youth. There are many signposts throughout the book that scream that this is not simply a case of ghostly haunting, and yet as readers conclude there is never a moment in which Model Home does not meet the standard of a horror story. Solomon is also particularly important as a voice in Jewish horror, a Black, post-colonial queer author whose address of Judaism breaks our boundaries of what we think “Jewish literature” is supposed to be. The fact that the story centers on a Jewish convert is itself a testament to how few examples of Jewishness actually exist in most Jewish novels. This may be why Solomon has been excluded from most Jewish books reporting (as well as her solidarity with Palestine, which is even mentioned in the text itself).

This first quarter I also tackled two books by Agustina Bazterrica, who became exceedingly famous a few years back when she released the dystopian cannibal novel Tender is the Flesh. Her short story collection Nineteen Claws and a Black Bird (2020) and the 2025 novel The Unworthy feel akin to Solomon's Model Home in that they sit uncomfortably on the edges of horror, and the collection is not genre exclusive. The Unworthy is another dystopian novel set in a religious order based on hierarchies and an accepted form of cruelty, something that might be uncomfortably familiar to many. Her writing style and focus reminded me of 2024’s Craft: Stories I Wrote for the Devil by Ananda Lima and A Sunny Place for Shady People by Mariana Enriquez (though darker) in that they shift back and forth between supernal and mundane fears, and Bazterrica seems especially unconcerned whether the terror is otherworldly or simply the anxiety that drives so many of our faulty decisions. It’s worth saying that Bazterrica’s writing style can be off putting for some. The Unworthy was, at times, difficult to get immersed in as it is written in fragments with an exceedingly complicated atlas of names and titles; a world being built without easy access. But with patience, you get what so seldom happens in horror: an entirely new existence to try and see ourselves in.

Coup de Grace, a novella from 2024 written by Sofia Ajram, was recommended to me as an analogue to Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves. While I think that comparison ultimately fails, I think the suggestion comes from the fact that Ajram captures a unique “architectural horror” where the external takes on the metaphorical quality of becoming lost in our own life crisis. Our character takes the train to where they intend to end their life. They descend into the underground territory and find a Maurits Cornelis Escher topology they cannot make their way through. Once we encounter their first co-character we think the book has established its format, but that is a mistake, and the text re-establishes itself several times across its short length. This is its strength and its weakness since some areas, particularly the earlier chapters, are stronger than others, such as those that close the book. Ultimately, I admit that I enjoyed it enough to recommend it, but its effectiveness may be entirely subjective.

I also went back to Nat Cassidy’s brilliant 2022 novel Mary, a prelude to his upcoming novel, When the Wolf Comes Home. This comes close to Rivers Solomon’s novel, at least in terms of enjoyment as one of the most engrossing, and largely amusing, horror novels I’ve read the past year. It follows our title character as she is pulled back into the orbit of an abusive aunt who raised her and the simmering violent theologies that sit underneath her history. It’s nearly impossible to talk about anything to do with the plot without revealing key secrets, but suffice it to say this funny-turned-gross-turned-gory book hits multiple sub-genres in a fashion that feels magically uncrowded (though it could be a touch shorter). Cassidy is a great example of an inventive horror writer with commercial appeal (or, at least, what should be commercial appeal) hits a big tent of readers.

I also covered the final issue of Weird Horror (#8) from Undertow Publications, another successful edition, yet with fewer standouts than previous months. Undertow has proven to be one of the most consistently inventive literary horror publishers on the market, best known for beautiful collections of venerable, if not particularly famous, horror authors. The best stories of issue eight are “To the Wolves” by Sasha Brown and “Fliers” by Gordon Brown, though there is an interesting slate and, as always, a fun essay from Orrin Grey.

Subscribe to the newsletter

I’d also like to point people to one thing Amazon has actually done right which is that they have been plucking quality genre writers for their Amazon Originals option on Kindle, where high profile contributor write long(ish) short stories you can read if you are a Kindle Unlimited or Audible subscriber (or I think you can purchase them for cheap if you are not). Last year I enjoyed their Creature Feature series with great stories by Joe Hill's "The Pram," Grady Hendrix' "Ankle Snatcher," Josh Malerman’s "It Waits in the Woods," Paul Tremblay's "In Bloom," Jason Mott's "Best of Luck," and Chandler Baker's "Big Bad," with Hill And Tremblay's as the best (though all were fabulous). This month I just began an earlier series of science fiction inflected stories and am reading great contributions, “The Backbone of the World” by Stephen Graham Jones and “Wildlife” by Jeff VanderMeer, both worth checking out. What’s especially nice is you can toggle from Kindle to Audible as you read. For those who don’t fuck with Amazon (you’re good people), I’m not yet sure the way you can read these, so maybe we can just get them pulled out of their software and posted online somewhere.

Over the next few months I’ll be digging into more comics and some books from Valancourt, who does a lot of reprint of long-lost horror that should have been classics (such as Hendrix’ Paperbacks from Hell series) and translations of international short horror, so I’ll be sharing more about them, as well as a feature about Tenebrous Press and a profile of different Undertow Publications titles.

I also wanted to highlight some good new nonfiction books people should have on their radar. First is Sophie Lewis’ new book Enemy Feminisms, something that’s a long-time coming. Lewis is amongst the most brilliant writers in the world (I don’t say it lightly) and this book is critical engagement jumping off from her work as a family abolitionist by looking at the reactionary voices operating under the guise of feminism, such as the increasingly threatening Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists (TERFs). She also did a related (and controversial) piece on feminist Zionism in Salvage a while back, which was so on brand for the book that I wondered if it was actually a piece that was originally in the text.

I would also recommend some great new titles from AK Press, including Southern Panther, a long-term collaboration project between New Orleans Black Panther Malik Rahim and my friend James Tracy. Rahim has a long history as a radical organizing, and in 2005 he was a central figure in responding to Hurricane Katrina and building the Common Ground Clinic with scott crow. AK Press also released a fascinating mutual aid anthology called Red Flag Warning: Mutual Aid and Survival in California's Fire Country, edited by Sani Burlison and Margaret Elysia Garcia. The book seems to focus on the Paradise fire and related mid-state devastations. People may remember, but AK Press, which is now located in Chico, California, was at the center of those "red flag warnings. Their collective was involved in the mutual aid organizing that sustained that community through one of the worst American natural disasters of the 21st Century. 10% of the sales of that book go to Mutual Aid Disaster Relief, which is, by my mind, still the most important cross-country mutual aid organization. Also check out AK Press’s anthology Rojava in Focus, which is a good and up to date volume on the Rojava revolutionary project.

Also make sure to check out Dean Spade’s new book, Love in a Fucked Up World, about how to heal relationships and build lasting bonds. I’m working on an article about the relationship between Dean’s work on repair and transformation and the building of vibrant communities of mutual aid. I would also recommend Peter Beinart’s new book Being Jewish After the Destruction of Gaza, which is a good summary of the internal chaos of understanding Jewishness in light of what is being projected on our identity by the Israeli state. I wrote this piece recently about Beinart’s book and the relationship other Jewish authors have had to the questions raised.

Stay tuned as I post a reading list of books on the Jewish left, which is what I am reading about most from non-fiction since I am preparing to announce a big future book project.

Subscribe to the newsletter