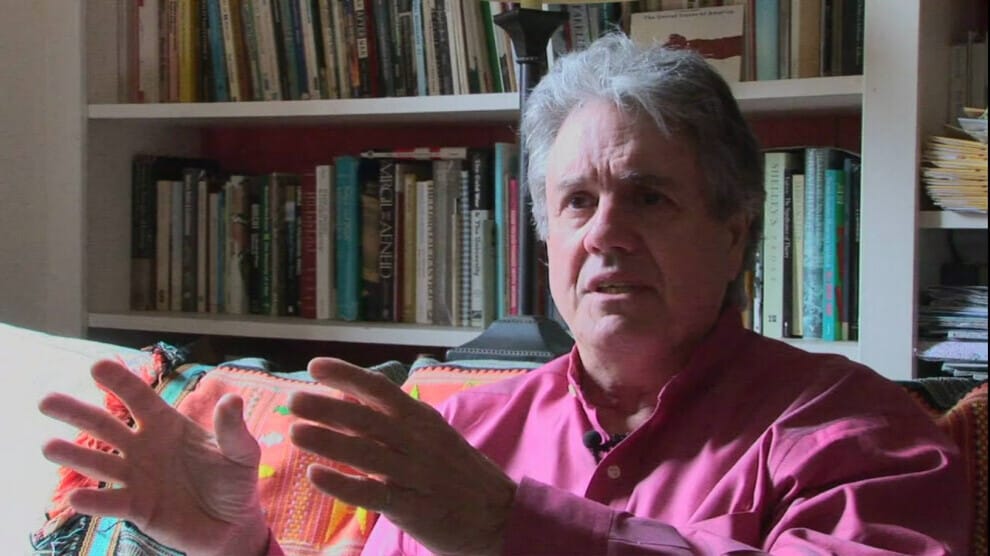

Revolutionary Love: An Interview with George Katsiaficas

We talked with Katsiaficas about his most recent essay collection, Eros and Revolution, released by Montreal’s Black Rose Books, about the passionate movement to confront power and construct a world beyond the borders and boundaries of the old.

As we are seeing the latest mass insurgency happening across the U.S., the most recent in what has been a rapidly accelerating two decades of increased mass uprisings, the energy found in the streets begs to be understood in its historical context. For the past forty years, scholar and revolutionary George Katsiaficas has attempted to hone in on the loving passion that drives resistance movements and to discuss what universal values and human connection these build on. By bringing his experience with social movements to bear, and particularly lessons from the Black Panthers to the April 19 revolution in Korea, Katsiaficas is driving at something shared by the insurrectionary mass subject that is responding not just to accelerating conditions of crisis, but the accumulated belief that something better is possible.

We talked with Katsiaficas about his most recent essay collection, Eros and Revolution, released by Montreal’s Black Rose Books, about the passionate movement to confront power and construct a world beyond the borders and boundaries of the old.

Shane Burley: For those uninitiated, what does this concept of the “eros effect” mean and what relationship does it have to the mass political awakenings that have occurred in recent mass movements such as the Occupy movement, Black Lives Matter, recent surge of rank-and-file labor organizing, and the movement in solidarity with Palestine?

George Katsiaficas: Although it is possible to discern this phenomenon domestically and locally, I first came to understand the Eros Effect on an international level. Pulling together years of research in 1983, I had a Eureka moment as I uncovered the specific synchronic relations of nationally defined movements to each other. A massive global wave in 1968 of spontaneous uprisings, strikes, and popular occupations of public space could not be explained in nationalistic terms. During this world-historical period, millions of ordinary people suddenly entered into history in solidarity with each other. Their sudden activation was based more upon feeling connected with others and love for freedom than with specific national economic or political conditions. No central organization called for these actions. People intuitively believed that they could change the direction of the world from war to peace, from racism to solidarity, from external domination to self-determination, and from patriotism to humanism.

During moments of the eros effect, universal interests become generalized at the same time as dominant values of society (national chauvinism, hierarchy, and domination) are negated. When the eros effect is activated, humans’ love for and solidarity with each other suddenly replace previously dominant values and norms. Competition gives way to cooperation, hierarchy to equality, power to truth. During the Vietnam War, for example, many Americans’ patriotism was superseded by solidarity with the people of Vietnam, and in place of racism, many white Americans insisted a Vietnamese life was worth the same as an American life (defying the continual media barrage to the contrary).

More recently, the eros effect now occurring on college campuses defies the government’s continual military support for Israeli settler-colonialism. Contradicting massive media barrages alleging anti-Semitism and false narratives of mob violence, people are constructing loving protest centers even while under attack by police and pro-Zionists. The rapid proliferation of the movement has left authorities bewildered, and their repressive response has only further spread the movement.

The sudden and unexpected character of uprisings is one of their defining features. The Black Lives Matter developed a new language and multi-racial solidarity across the United States. In a few months, the largest uprising in US history changed society through the participation of tens of millions of people. After decades of declining union membership, more recently, we have seen a wave of labor unions mobilize and win better working conditions and salaries. In my lifetime, I never thought I would see such a great movement in solidarity with Palestine as is today sweeping the US. Despite the repression against it, the movement has revealed Israel’s murderous brutalization in Gaza and the racist character of Zionism to the world. More and more people understand that the Jewish state exclusively values Jewish lives. Such a chauvinistic concept is, of course, mirrored in the United States, where an American life is considered much more valuable than an Afghani or Iraqi. Palestinian resistance again proves that people’s need for freedom is unstoppable.

SB: Part of the effect of mass uprisings is not just on the political systems they oppose, but on the self-conception of those participating in the rebellion itself. How do rebellions reshape the consciousness that many communities have?

GK: You make a good point. Uprising should not be viewed as objects but as subjects. There is a distinct difference between the two. Subjects are living organisms able to reflect upon their existence, to develop lessons based on experiences, and to act differently in future situations. Movements should be understood as dynamic forms of life in which developmental stages can be seen. It is sometimes very difficult to notice these stages from inside the movement. I would compare this to growing up around a child. Suddenly when a visitor returns after a long time, they can notice very distinct changes in the child’s body and actions, whereas for people in closer proximity, these changes, while evident, were not so noticeable.Uprisings have a number of effects, not only on their participants, but on all portions of the population. They provide people with a sense of their own power, with an understanding that we do not need to ask the rich and powerful for the changes we want in our lives as much as to make those changes directly and to live them.The universalized character of uprisings inspires more specialized mobilizations. People refuse to submit in their everyday lives to long established forms of control and domination. Uprising are important forces in unleashing freedoms that are boxed up by existing political and patriarchal forms of domination. In the string of Asian uprisings from Gwangju 1980 to Jakarta 1998, we repeatedly saw the same phenomenon: working-class movements arose along with sudden activation of other segments of the population, such as women, sex workers, indentured servants, and professionals.

Subscribe to the newsletter

SB: What do you think the long-term influence of the Black Panthers has been on American political radicalism? What relevance does that history have today?

GK: The Black Panther party was the most radical political formation in the United States in the latter half of the 20th century. They understood the importance of building a rainbow coalition, and they enjoyed support from the grassroots of every constituency in motion in the late 1960s and early 1970s. They inspired the formation of Panther groups in more than a dozen countries and formulated a vision of what a free world would look like.

For movements today, the gun-toting image of the Panthers is no longer relevant, nor is it accepted. Perhaps that is for the best, especially since the FBI and police are not systematically murdering movement activists as they were when the Panthers posed what J. Edgar Hoover called “the greatest threat to the internal security of the United States.” Sadly, there are still Panthers in prison as a result of the state’s overwhelming response to their courage and conviction. Today’s decentralized movements do not give the government a single target to attack. Certainly that is for the better.

SB: The April 19 revolution may be even less discussed amongst U.S. radicals. For those who remain uninitiated to this history, what is its significance to global struggle and what lessons does it hold for movements in other parts of the globe?

GK: Only seven years after the armistice that ended the hugely destructive Korean war, the people of South Korea overthrew their American-imposed government. Sadly, it took the lives of almost 200 young people for the movement to succeed, Happily, the army sided with the people in the streets and helped stop police and right-wing thugs from continuing to attack and murder people. That the army can play a progressive role is perhaps its most important legacy. In 1960, it also helped to inspire movements around the world, especially in Turkey and the United States.

In 2010, I spoke with Tom Hayden, one of the main authors of the Port Huron Statement, the founding document of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). He remembered his feelings when he first heard the news from Seoul: “I was exhilarated when I saw young people our age overthrow the dictator Syngman Rhee. Through that movement, I learned the history of the Cold War for the first time. Those events challenged our naive belief that our parents were fighting for a free world. I can tell you that movement helped inspire SNCC [the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] and the black movement in the South. Two days after Syngman Rhee’s forced resignation, SDS held its first meeting.”

SB: In terms of assessing the trends of global struggle, are you optimistic about the efforts of revolutionary movements now?

GK: While the global media portray right-wing billionaires and the dangers of extreme fascists, beneath the surface of these false narratives, revolutionary movements continue to develop. When racists mobilize, anti-fascists’ counterprotests are many times larger. Although often unacknowledged or rendered invisible, liberatory movements have a massive base of support that becomes visible in specific moments. This is a reason for optimism.

On the other hand, the Black Lives Matter movement was the largest mobilization in the history of the United States yet it died down quite quickly. Was that because of improper leadership? I think that’s not the only reason. Contemporary social movements erupt suddenly and die down very quickly in many countries. There are ways to sustain their vitality. Cultivation of grass-roots forms of decision-making is vital. We saw recently in Sudan how democratically-constituted councils with direct connections to mobilizations continued to inspire and sustain people to act against injustice. However, we can also see in Sudan that ruthless armed militaries can murderously interrupt freedom movements. The global rush to arm nation-states with weapons of mass destruction and massive armed forces and police is an ominous trend.

Subscribe to the newsletter

SB: There seems to be an increase in mass uprisings at a time when formal organizations still struggle to maintain continuity. Do you think that this means that the types of political forms that people are turning to are changing? Does this present opportunities for the kind of revolutionary social transformation you indicate with the “eros effect?”

GK: As we can observe with the Black Panthers, centralization can be both helpful and problematic. Movement activists today believe in decentralized formulation of tactics and organizations, in grassroots democratic councils as opposed to Leninist central committees. This is extremely important and must be understood in order for movements to progress. The Kurdish movement’s evolution, its rejection of nationalism and embracing of empowerment of women and local communities is an indication of the future of movements everywhere.

Popular uprisings develop according to a logic of their own. Since 1968, we have seen distinct waves of globally important insurgencies: from the nuclear disarmament impetus of the late 1970s, to the overthrow of Soviet regimes in the late 1980s, the wave of Asian Uprisings from 1980 to 1998, the alter-globalization mobilizations of the late 1990s, and finally the Arab Spring/Occupy in 2011. These uprisings did not take place because centralized organizations called their supporters into the streets but because millions of people decided for themselves to take action on issues they themselves chose.

SB: What opportunities does the left have when their objective is less to influence state policy and more directed towards counter-power?

GK: With the United States funding two major wars and instigating a global conflict with China, the urgency to change government policies is evident. Dislodging billionaires and their sycophants from positions of power has never been more needed.

At the same time, people working to change society from within the government should consider whether or not their actions will at best rationalize a fundamentally unjust political system. I believe that to end global capitalism’s destruction of the environment and the Pentagon’s perpetuation of wars requires dismantling the state as we know it. In 1970, the Black Panthers convened a Revolutionary Peoples’ Constitutional Convention that sketched the outlines of a free society. We have many models for forms of freedom, including the concept of bio-regional coordination and Murray Bookchin’s notion of municipally based power.

SB: What are the shifts you are seeing occur in global uprisings, and what new opportunities are opening up?

GK: The recent upsurge around the world and support of Palestine is incredibly uplifting to me. It is the latest eruption of the eros effect. The continuing mobilizations and camps demonstrates once again that grassroots thinking is far more intelligent than our rulers and their media. In the 1980s, when I was doing work around Palestine in the United States, I felt incredibly isolated. We were branded as anti-Semitic and roundly condemned. Today people see through the weaponization of charges of anti-Semitism, they reject Israel’s claim to be based upon human rights and freedom. Of course, this will be a long struggle. The Crusaders of the Middle Ages controlled portions of the Middle East for nearly 200 years, but they were finally expelled.

Today, Israeli genocide against Palestinians is in plain sight at the same moment as The New York Times instructs its journalists not to use the word Palestine, and the US vetoes Palestinian membership in the UN. The US government is entrenched in its militarism. The need to change the war-loving gerontocracy in Congress has never been greater, while the rules of the political game have never been less oriented to peoples’ needs.

SB: And, lastly, what lasting effect has Herbert Marcuse had on your thinking?

GK: As a man I came to know, Herbert helped me to relax in the face of unrelenting attacks from “comrades.” I remember one incident in particular when I had gone to a Halloween party at the house of a nearby collective in Ocean Beach. From the moment I entered the room to the moment I left, people engaged in various forms of passive aggression. I was spooked that Halloween evening! Later, I discussed my feelings with Herbert. He calmly informed me that they had invited me to insure that they would have a moment to vent their group emotions on me. He also guessed there was more going on than met the eye. He hit the nail on the head. As I discovered years later, these people had been informed that the FBI was photographing everybody who came and went from Red House (the commune where I lived), and they never told us about it. They even discussed telling us and decided against it.Herbert’s writing has also had profound effects on me. I think especially of his emphasis on the meaning of revolution to include the transformation of our unconsciousness, the necessity to transform even our instincts in order to live in a free society. The International Herbert Marcuse Society (MarcuseSociety.org) and my website (eroseffect.com) provide details on his continuing relevance to revolution.

His work anticipated the collapse of the Soviet Union. He realized the importance of Nature as an ally of revolution long before the ecology movement arose. In my view, his work remains and will continue to be incredibly important.