The Best Books of 2025

Read my list of the top books released in 2025.

It is nearly impossible for even the most voracious reader who is anything other than a full-time book reviewer to put together a true top ten list. First, recently released books rarely make up the majority of a year’s meaningful reading. Artificially shrinking the pool to only new releases is a recipe for diminishing enjoyment, since you are less likely to find books that match your tastes. And it is exactly those personal preferences that make it unlikely any such list will resonate far beyond your inner circle.

Still, I have tried to do this anyway. I did tend to lean toward 2025 titles this year, and when there was a choice, I favored variety over more of the same. If you want to read just my favorite horror books, those appear in the next list. And if you want to hear more about this year’s reading more broadly, I will soon post lists focused on the conflict in the North of Ireland, Israeli politics, and Syria.

So take a look at this list, which reflects a fairly wide spread of what came out this year. I am already beginning to read into 2026 with a handful of recent pre-release ARCs. What has been heartening is that in a year defined by unprecedented censorship and attacks on free expression, the long-form book has remained a challenging medium. Its economic and social limitations may even help insulate it, at least somewhat, from the pressures toward rhetorical conformism now emanating from the highest levels of state power.

Another incredible look into the ferociousness of modern fascist street politics by international journalist Patrick Strickland, this one told from a country he calls home. Strickland’s reporting career began in Palestine, later leading him to work with Arabic-speaking immigrants on Greek islands searching for pathways to refuge in Europe. This was a moment when Golden Dawn became a leading political force as an openly neo-Nazi party, something far to the right of even the broader, near-fascist world of national-populist politics in Europe. What Strickland does is place us directly within these historical moments, highlighting their unsettling similarities and implications for the rest of us: in the heart of Europe, clear-eyed fascist politics built entirely on retributive violence took hold among an ailing working class.

9. Picks and Shovels by Cory Doctorow

This is the second Martin Hench novel to make the list, a testament to Cory Doctorow’s ability to inject energy and familiarity into his work. The book traces Hench’s early life, from experimenting with computers at Harvard to studying accounting and eventually heading to Silicon Valley. Along the way we encounter a computer company run by clergy whose scam locks religious communities into planned obsolescence. Three religious women leave their communities and form a competing business retrofitting computers to work across platforms. While this premise may sound dry, the novel is lively, character-driven, and deeply affectionate toward its ensemble cast. As with Doctorow’s other work, it critiques the capitalist logic of the tech industry, showing how potentially liberatory tools are transformed into engines of extraction. More than anything, this is a hopeful and satisfying thriller about what compassionate, intelligent people can build together.

Subscribe to the newsletter

8. The Next One Is for You by Ali Watkins

While there is no shortage of books on the Irish Republican Army and the Troubles, few serve as an ideal entry point for newcomers. Many are academically dense, journalistic but dated, politically dubious, or demand significant background knowledge. A good book on the Troubles does not attempt to capture everything but instead provides a clear, compelling introduction before committing to its particular focus. That is precisely what The Next One Is for You accomplishes by examining American Irish expatriates who helped build NORAID in support of the IRA’s campaign for a united Ireland. The book features a strong ensemble cast and balances lyrical prose with brisk pacing, making it accessible to both newcomers and those deeply familiar with the subject. After reading nearly twenty books on the topic this year, this remains one of my favorites.

7. The Staircase in the Woods by Chuck Wendig

A lengthy horror novel by Chuck Wendig has been something I’ve considered dependable since I read The Book of Accidents a couple of years back, so I was sold as soon as this was released. The Staircase in the Woods delivers a twist about a hundred pages in that left me feeling blind as I passed through the remaining rooms. The book is a smartly drafted meditation on trauma and its impact on relationships, creating a consistent and deeply metaphorical world geography that, just as it threatens to overstay its welcome, completely redefines the narrative. Wendig has a Steven Spielberg quality of textual mastery, and while this is not exactly an experimental work of metafiction, he so deftly draws on classic fantasy-horror storytelling that you forget you are reading something built on those bones. A television adaptation feels inevitable.

Despite still appearing on horror lists, this is a book where fear itself is mistaken for genre. O Sinners! is a restrained and engaging novel about grief, memory, and the dual burden and opportunity of faith. It follows a journalist embedded in an alleged cult, spending months reporting on a single article and entering an extended debate with both a guru and his followers over the legitimacy of the group’s claims. While there are quasi-supernatural elements in the background, they remain largely incidental. This is a novel about people talking, changing, and processing something deeply familiar. A bold and serene examination of a particularly American way of avoiding emotion by building a religion.

5. At Dark, I Become Loathsome by Eric LaRocca

If LaRocca writes it, I will recommend it. This is perhaps his most ambitious and offensive work, one that astonishingly avoids collapse and instead remains vulnerable and true to the Barkerian horror tradition he is rebuilding. It begins with a man processing grief over his wife’s death by allowing people to pay him to be buried alive for thirty minutes and spirals into a brutal series of narratives, both in the primary plot and in stories within the story. LaRocca’s limitations with the novel form are evident in his shifting perspectives and simplified characters, but those qualities are also part of his distinctive charm. This is an easy book to point to when explaining that LaRocca is not for everyone, yet it was written with film adaptation in mind and will likely reach a wide audience. An astounding and terrifying writer, and perhaps the purest embodiment of what horror fiction can do on this list.

Subscribe to the newsletter

4. Being Jewish After the Destruction of Gaza by Peter Beinart

Beinart’s lyrical lamentation on the genocide in Gaza is one of the strongest contributions to what has become a cottage industry of books grappling with the most violent period in Palestine’s history. His Judeocentric lens spends more time on Jewish self-understanding during this conflict, parsing history, texts, and traditions through the prism of his own family’s experiences emerging from the Holocaust and South African apartheid. This is not the most radical book in the field, nor does it need to be. It serves a particular role in helping manage the weight of Jewish identity amid this rupture. While there has been criticism of the book’s Judeocentric focus, that emphasis is also its strength. Beinart excels at articulating Jewish identity and helping to chart a break with what he calls the American Jewish establishment, a rupture that has accelerated since October 8, 2023 and reached a zenith in 2025 as networks of counter-Jewishness began to coalesce. This is a short, warmly written book about a movement born of immense violence and the need to understand our place within it.

Moonflow by Bitter Karella was maybe the most fun I had all year and one of the best examples of the surge of great trans horror novels over the past couple of years. This is Karella’s first full-length novel, and she nails the pacing as she tells the story of a psychedelic mushroom retailer sent out by a friend to find a rare mushroom species. Instead, she finds a TERF-y green goddess cult run by a woman breastfeeding raccoons, and that is only within the first hundred pages. The book has a great pulpy feel but employs folk horror to discuss threats both inside and outside of society.

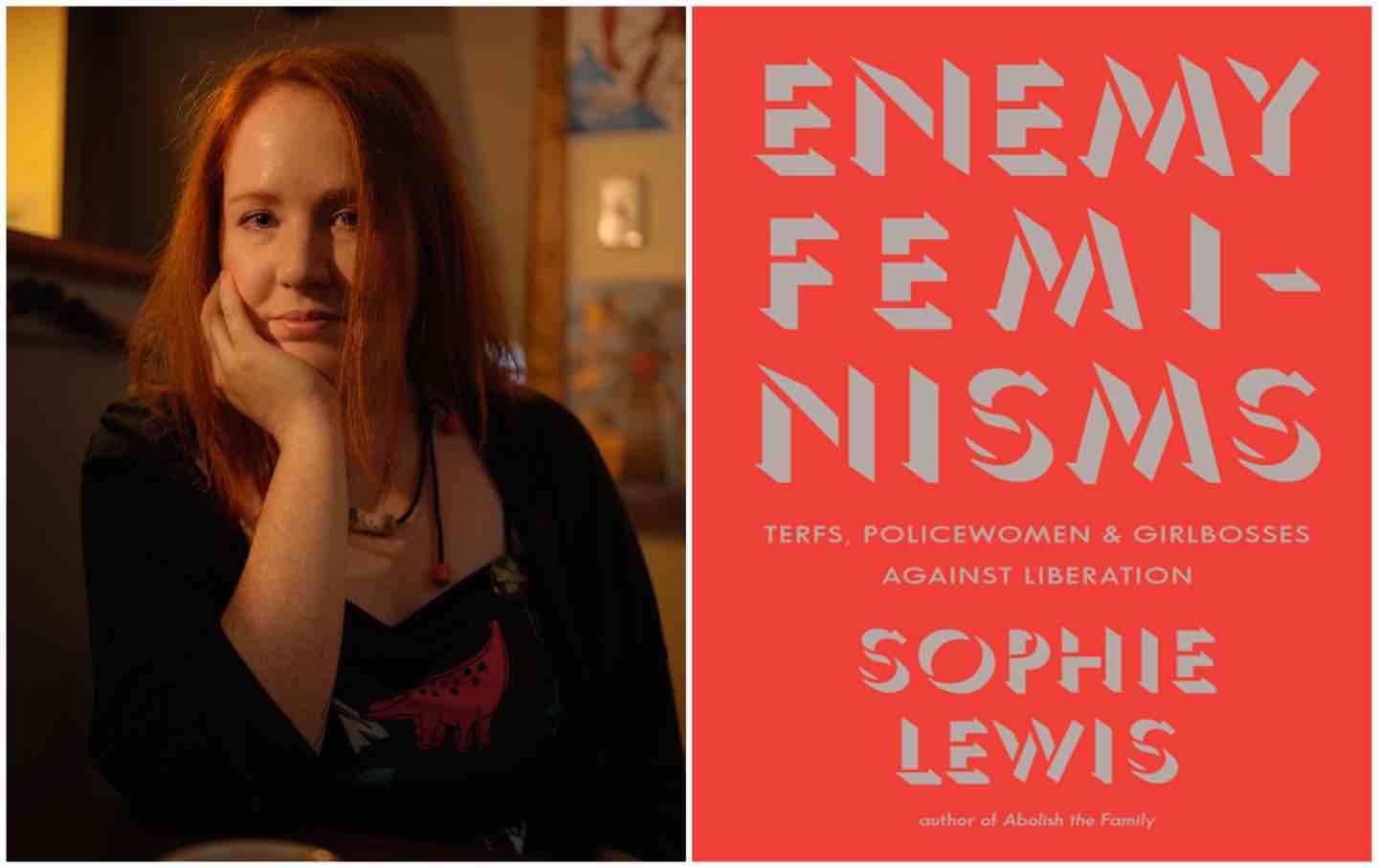

2. Enemy Feminisms: TERFs, Policewomen, and Girlbosses Against Liberation by Sophie Lewis

Every book Sophie Lewis releases is underwritten with subtle brilliance, making it hard to do anything but praise Enemy Feminisms. Lewis traces feminist history by examining recurring character types and distortions of feminist ideals. She defines feminism as the “communization of care” and rejects the comforting idea that reactionary feminists are not real feminists. They are, just as bigoted leftists are still part of the left, and dealing with them is our responsibility. Lewis approaches these movements with a level of vulnerability and honesty that is rare in modern political writing, examining anti-sex-work feminism, feminist arguments against antiracism, and modern trans-exclusionary radical feminism, a tendency committed to stripping any liberatory potential from critiques of patriarchy. What sets this book apart is Lewis’s wit and rhetorical warmth, lending empathy to discussions of genuine political adversaries. I will recommend anything she writes and eagerly await her upcoming book on children’s liberation.

While this was a book I waited until the end of the year to read, it’s one that I’ll carry with me long into the New Year. The book starts with a chance meeting between two people and a conversation that reveals similar tragedies, each seemingly tied to a shared strange figure who briefly emerged to photograph their loved one before disappearing into the mist. That meeting sends one of them on a global journey to speak with others who have had this same encounter, each watching a friend, relative, or lover descend into an enraptured madness, made obvious by their bodies reversing their features. The book slowly unravels as a story about loneliness and survival and asks what the meaning of life is if it depends on the death of others. It’s hauntingly written by Susan Barker who I encountered just a couple of weeks before starting Old Soul by reading her story “Fight, Flight, Freeze” in the 2024 British horror anthology Of the Flesh, just in paperback this year.