Towards a Diasporist Jewish Future

What does it mean to bring a radically new, authentic, and even traditional lens to Jewish practice? And how can we root it i the diaspora?

While Jewish history is so often recounted as a linear pathway—usually pointing toward and ending with the creation of the State of Israel—it’s easy to forget that it’s a tradition of cycles. The Torah is read in weekly increments, called parashiyot, and the Hebrew calendar acts as an arcane map to locate the spiritual tools left by ancestors. Whether they’re pathways to growth and healing, to remember the liberating stories of the past, or for getting wicked drunk with friends, Jewish ritual is based on sacred time, so the easiest way in is to jump into the beat of the yearly cycle.

Indeed, as Israel’s genocide in Gaza continues and the politics of Israel are injected into nearly every vessel of Jewish life, a growing number of Jews are reclaiming the tradition and asking themselves: What’s left once we detach from nationalist politics and the stale, calcified institutions that no longer serve us?

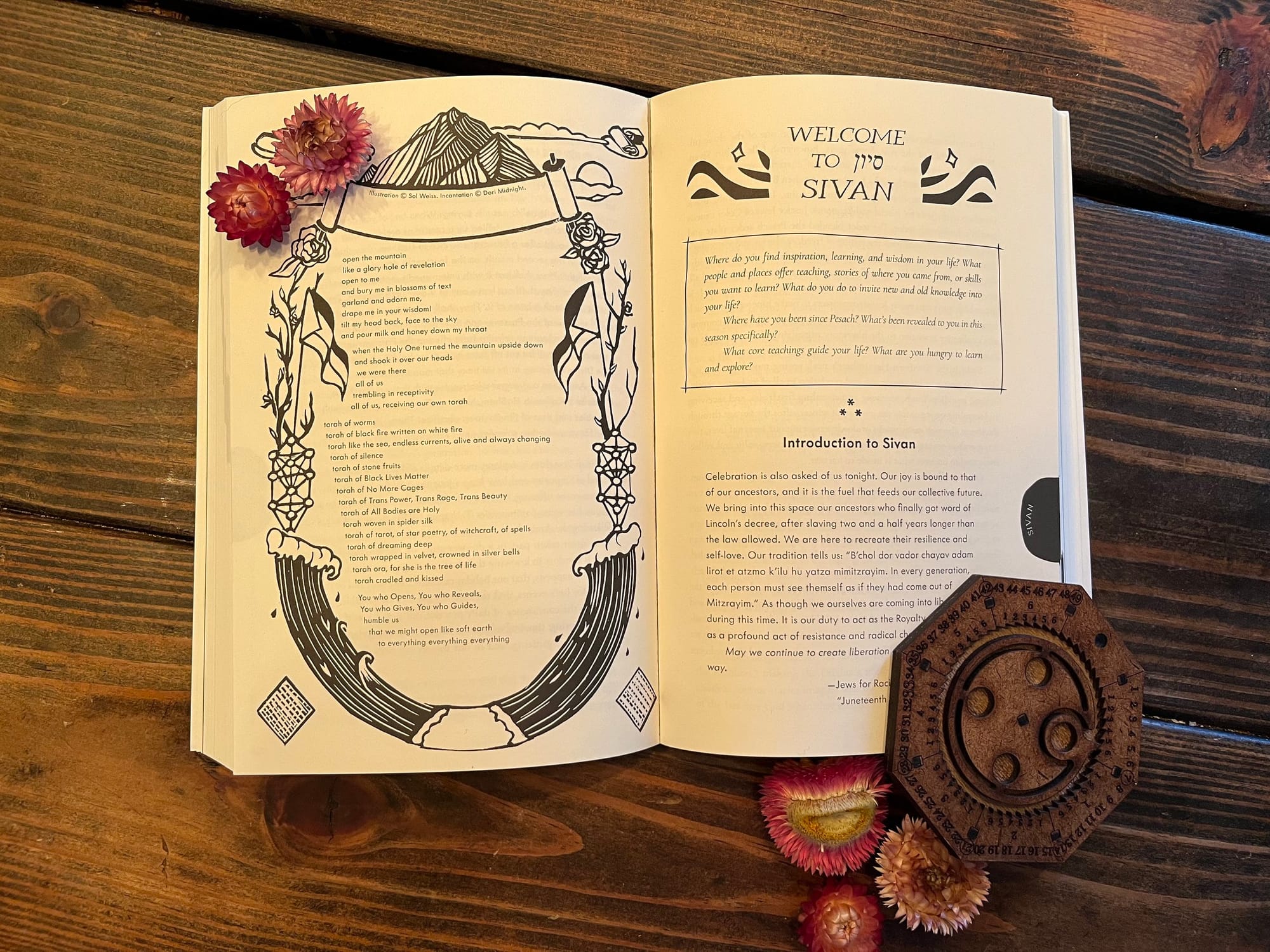

What Rabbis Jessica Rosenberg and Ariana Katz imagine in their book For Times Such as These: A Radical's Guide to the Jewish Year is something wholly larger and more earth-shattering than the vision of Judaism so many have been offered in suburban Hebrew schools. Built out of the Reconstructionist tradition and with an eye towards the intersection of Jewish life with the kind of radical community organizing both authors have been involved in, their new book takes us through the year’s holiday and Torah cycles, and launches us into what they call a “Diasporist” vision of a revolutionary Jewish future. RD talked with the authors about the inspiration behind the book, the social forces they’re hoping to capture, and what kind of Judaism is possible for those looking to reinvent their communities just as those who came before did.

Shane Burley: Where did the idea for this book come from and what was the vision you had for it?

Ariana Katz: The first thing to say is that this book was submitted before October 2023—and yet, I think, it’s as relevant as ever. It’s still a Jewish year, and what it has meant to do Jewish in the wake of Israeli-perpetuated genocide is pretty humbling and existential. So our hopes for this book were to narrate Jewish life for everybody—but especially those on the Jewish Left who are looking to integrate our political work and spiritual lives. And then to also agitate Leftists about Judaism and antisemitism and offer something to people with different entry points. Since the beginning of the genocide in Gaza we’ve seen an increased desire for a Judaism beyond Zionism.

The book is actually reclaiming the wisdom of our tradition from Zionism rather than creating something new. The inflection of political Zionism in every part of Jewish experience has made access to Jewish life impossible if you don't abide by that one Jewish political opinion. It feels like reclaiming our inheritance—and, one might say, our birthright—and offering it back.

Jessica Rosenberg: We started dreaming of the book when Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz, who was an inspiration as an organizer and writer, died. We had already been working on the Radical Jewish Calendar for years, so we wanted to make something for our community. The calendar and Jewish time is such an entry point for people to re-engage with Jewishness. You're not going to start davening mincha, you're going to start by making a Passover seder. We began writing in 2018, and we're part of so many radical Jewish communities who don't have the tools we need. We went to rabbinical school, so we thought we could get the goodies and bring them to people who are searching for them.

Subscribe to the newsletter

Why do you think so many Jews don’t have these tools?

JR: It's from genocide, antisemitism, assimilation, and Christian hegemony, on one hand, and patriarchy and homophobia, on the other. There's a whole generation of post-World War II Jews who assimilated into Christian society and went to Hebrew school the last Tuesday of the month—and it was stilted and boring. Or when they experienced Jewishness it might have felt homophobic or misogynist. The fact that people are now clamoring for their Judaism is really interesting.

The book carries readers through the Jewish year, holidays, rituals, Torah, and everything that comes with it. What kind of experience does that offer, following along with the Jewish year?

JR: The Jewish calendar is based on both a liberation story and the Earth's seasons. All of our holidays are the story of where we came from and they aligned us with the seasons we were in; and the core of the holidays is in bringing people together. They’re not something you can really do alone. In the book, we tried to bring the core mitzvot (commandments) and then place the minhag (customs) on top of that.

In doing so I feel like I gained a new understanding of how feeding people and tzedakah and telling stories about where we came from—those are the core activities of the year. For all that I believe in and want to be true in the world, people feeding each other and telling origin stories and coming together regularly to do that—that's the activity.

My personal theologies are around interconnection between people and the earth—that’s what God is to me. God is felt and experienced in the sense of interdependence. If I were going to answer what the best way to experience God is I would say sing together and feed someone and be fed by someone.

This term, spiritual technology, is used throughout the book to discuss Jewish ritual and practice. What does that mean?

JR: I think it's a way of pulling the curtain back on the mechanics of a spiritual experience. There's different traditions where people go off alone in the woods, traditions that are in silence, traditions that are of song. Spiritual technologies are the tools and mechanisms that make up a spiritual experience and often go unnamed. One of the things we’re trying to do with the book is empower people to seek out and pursue the experiences and ritual life they want. To show them that they can cultivate practices that resonate with people. Spiritual technology is a way of showing that Jewish tradition is human created. Spiritual practice in general is like breathing—humans want ways to connect to each other and the natural world. But there’s a lot of choice in how that happens. This term demystifies that.

AK: When I teach Introduction to Judaism I often reference a Wile E. Coyote who gets smashed by the anvil of Judaism: it's so big and you see it coming and you can't get your arms around it—so it crushes you. That's because it's a millennia old civilization of politics and culture and language and faith and history and more. But when you talk about spiritual technologies, at least for me, it's trying to explain the different components that make up what we're doing. It's an attempt to quantify what’s unquantifiable.

Anti-Zionism is one of the book’s starting points, but it moves past that quickly by instead focusing on what a meaningful Judaism can look like right now. How did you construct a vision for that and do you think there’s an emerging new Jewish movement happening right now?

AK: There is a new Jewish world blossoming over the last decade that’s very firmly standing on the shoulders of the decades before it. There’s just an explosion of culture workers and religious leaders and people who are creating and thinking and making and claiming space that’s combining a diaspora politic, a liberatory solidarity Judaism often centering queer and trans people, and, at least in the US, an acknowledgement, ownership and rejection of the ways that Ashkenazi American Jews have colluded with whiteness and harmed Jews of color. It feels like a profound and shifting moment, and I feel the moment of the people who’ve been doing this a bit longer and are bridging the generations.

JR: If you’re trying to have a 365-day Jewish life, you'll want more than what you just use in public protest. That doesn't seem like a dig to me. We wanted to have better ritual, and I think that’s what a lot of people are doing. We just got the privilege of putting our name on a book about it. I do think what's in the book is reflecting many people's anti-Zionist Jewish life, which is more than just Zionism and Palestine. Anti-Zionist Jewish life includes people who care deeply about farm and food, and other political movements, so that plays a role as well. Before I was anti-Zionist I was a young, queer feminist—but anti-Zionism was my entry point to anti-capitalist, anti-nationalist and eventually anarchist politics.

What is this concept of Diasporism that you introduce in the book and how does it guide your Jewish vision?

AK: As mentioned, so much of the initial desire to write this book was inspired by Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz, of blessed memory, and her work on Diasporism. We are, and always have been, a multivocal, multi-ethnic, multi-national and international people. We have an obligation to both sustain that history and sustain the places we live, amongst both Jews and non-Jews. Off of that legacy there’s a sense of not defining ourselves by what we lack, which is a little bit ironic considering diaspora inherently means far from the center. But the difference between diaspora and Diasporism is a commitment to the places where we are, not because we wish we could be somewhere else.

One idea that’s become fraught given its implementation by the Israeli far-right is the concept of Jewish peoplehood, Am Yisrael, or even Jewish particularism. How do you approach the notions of Jewish peoplehood?

JR: The historic fight is between the universal and the particular, but I've been trying on the idea that the actual struggle we need to have is between supremacy and specificity. The problem is supremacy, and the antidote to that is everyone's specificity. The book is all about Jewish particularism—it's just not Jewish supremacy.

AK: What I return to is that this is the legacy I was given. This is what my mother taught me in the kitchen, what we argued about at the dinner table, and this is the community that raised me. I don't think it's better or worse than any other thing you could be given, or find yourself drawn to or inherit. My ancestors are flawed and incredible and everything in between. So I don't fear particularism, but I do fear supremacy, and I think that being able to root deeply in what is ours makes us more able to connect to what is not.

There’s a lot of religious and cultural sloppiness when people don't feel nourished and connected to any practice or tradition, whether it's something you're raised in or something you find. I think as much as we need to be uprooting our Jewish supremacy, I do think that Jewish uniqueness is important.

When I say kiddush, the traditional text says "who chose us from all other nations." But the Reconstructionist version gives us a text that scans to the same rhythm, but says "who chose us to your service." What I say is slightly different: "who chose us with all other nations."

JR: We talk about ahavat Yisrael, love of a Jew for another Jew. If peoplehood helps you take care of people, then great. There’s a part in the book where we talk about why we work with obligation as a Jewish concept that I think has some powerful anti-capitalist magic in it because it acts as a counter to individualism. So I think Am Yisrael has the potential to be a practice to help you love and care for people you don’t like. The question is then how you can extend that to other people and feel it with a larger human, planetary community.