Tu B'Shevat and Speaking Through Trees

Like most things in Judaism, trees are rarely just imposing plants. The Jewish holiday Tu B'Shevat powerfully locates the pathway God takes through us, from this distant and unknowable force into the bittul, the transcendent materiality of our bodies and lives, taking root through Torah, wisdom, and, ultimately, the action of mitzvot. Like a tree we are said to bloom when this energy is channeled, witnessing the fruits of this process not just intellectually but the actual, material healing in the world that should subsequently emerge. This is a particularly illustrative example of why Jewish tradition speaks so deeply to materialist sensibilities, because it is an intuitive folk narrative for the magical process that occurs when learning translates into the kind of action that affects change.

Tu B'Shevat, the “Rosh Hashanah for trees” held every year to celebrate our forests, has a seder similar to that for Pesach. Just as the annual commemoration of our exodus from Egypt, we use a type of haggadah, a story book, to take us through the seder ritual in honor of the trees and the rooting of Jewish life across the globe. "We celebrate the rebirth of nature and the rebirth of our homeland, Israel," reads Branching Out: Your Tu B'Shevat Haggadah, one of the more popular haggadot for the holiday and published by the Jewish National Fund (JNF). The first year I tried to hold a Tu B’Shevat seder, this was the haggadah I found, one that promises both to be simple and concise, but also to combine spirituality with environmental consciousness. The haggadah is one small piece of what has become a major holiday for the JNF, arranging everything from trips to Israel to various events claiming to tie Judaism to the Earth in general, but to the soil of Eretz Yisrael more specifically. A key part of their celebration is an invitation for Jews from around the world to plant a tree at home and, perhaps more importantly, in Israel. In a way that will “link themselves with Israel,” the tree planting is about the reclamation of land and soil, a proxy for national identity, so the tree stakes its claim not to the reparation of the biosphere, but to the land known as Palestine.

The Jewish National Fund is itself perhaps the primary institution of the Zionist project, an organization whose function is to buy, hold, and ultimately transform land, specifically for Jews to settle. The JNF remains the largest Israeli landowner, a corporation profiting from space whose indigenous inhabitants were forcibly removed, lending to its controversial status. Organizations like Independent Jewish Voices have fought to have the JNF stripped of its non-profit status in Canada. The organization has been regularly indicted as a “greenwashing” project, both that its environmental measures are largely lacking and that they are used as a cover for their actual project of land capture. The JNF tries to outmaneuver Palestinian land buyers with the intention of creating Jewish hegemony in indigenous Palestinian regions, all under the guise of green charity. Since 1967, well over 800,000 olive trees have been destroyed, countless fruit trees uprooted, the destruction of Palestinian gardens and wild lands.

The logic that fuels the JNF’s work is decidedly the same type that embodied early Zionist romanticism: a land without people for a people without land. This is why there is such a dissonance between much of the Zionist perception of the JNF and its reality: it was not a land without people, so then what does it mean to take, possess, and rebuild land? That requires, by definition, the expulsion and eradication of the native populations that once inhabited it, a project known as settler colonialism. There are two counter arguments used to challenge the claim that political Zionism was a settler colonial project.

Subscribe to the newsletter

The Jewish National Fund is there to create Judaized localities on top of existing cultural, linguistic, and political spaces. This process is incredibly clear in Zionist historiography: “draining swamps,” building Jewish agricultural bases, and building self-identified “settlements.” Nestled deeply in the notion that galut, exile, had stripped Jews of much of their dignity through a “degenerating” diaspora existence, this early Zionism had a “back to the land” mentality focused on creating agricultural settlements and kibbutz, collectively managed enterprises, usually farms. Even the Zionist left saw this in exclusivist Jewish terms: Avoda Ivrit, Hebrew Labor, meaning only hiring and including Jewish workers. While this was sometimes framed as a way to prevent the Jewish exploitation of Palestinian laborers, in reality this was a piece of the separatist politics that saw Jewish safety in our apartness from Gentiles. This process was not just about the social categories that sat atop of the land, it was about the land itself. Perhaps the most famous, and in a lot of circles that most celebrated, piece of the Jewish National Fund’s program is their “reforestation” efforts.

Reforestation is itself a process of rebuilding once destroyed forests, such as efforts across the Pacific Northwest to reconstruct forests leveled by clearcutting. Reforestation is simply the building of new forests, usually with a sense of the role trees have in repairing a chain of habitat, food sources, and water integrity. Reforestation is an incredibly valuable process to undo ecological destruction and restore balance, and it holds a radical solar punk dimension to it. But while the JNF’s project is often referred to as reforestation, it more accurate to say that it is “aforestation,” which is the “the artificial establishment of forests by planting or seeding in an area of non- forest land.” The JNF’s project of planting what has amounted to nearly three million trees in its life is a process of bringing in non-native trees and building forests where there were none, often bearing some resemblance to the forests Ashkenazi settlers might have experienced in earlier centuries. This takes two forms of Jewish memory and hybridizes them: the distant religious memory of Torah, now connected to the colonial homestead in Eretz Israel, and their more recent haimish in Eastern Europe. In this way, the emotional reality of these memories unite to become one, the Palestinian land now becomes instantly familiar and tugs on every layer of remembrance: historical, spiritual, familial.

There are certainly arguments for aforestation, which is why many environmental organizations, particularly Jewish ones, celebrate these multiplying forests. But it is also a fundamentally outsider project whereby the indigenous character of the land is reformed to adapt to the settler population, a type of colonial spearhead meant to not just take the land from its inhabitants, but even to strip out the memory of what once was. This is best seen in the attack on Palestinian olive trees, which are a key part of violence in the West Bank settlements, where olive trees are uprooted and replaced with oaks and almond trees, amongst other non-native species, a sign that this Palestinian land is now Israeli. One report put out by the Society for Protection of Nature recast the JNF's reforestation efforts as an attack on biodiversity and ruining regional ecological stability. This adds pause to the claim that the JNF’s project is an environmentally prudent one, which then begs the question of what the purpose of the trees are if not to stabilize the biosphere. The trees spread across the lands, themselves a type of settlement, changing the soil, water, fauna and even local atmosphere. It is now a land without people waiting for a people who once had no land.

The JNF’s afforestation is heavily tied to the growth of the Jewish environmental movement, and the reclamation of Tu B'Shevat. Because Tu B'Shevat celebrates trees, and the JNF has implanted the notion that they are mobilizing trees to stabilize Jewish life, they have colored the efforts of the Jewish left to use the holiday as an environmental cipher. There is no doubt that this is, in a larger sense, an incredibly powerful unification of environmental and spiritual conscience. This is part of the process of bridging material and spiritual concerns into a more dynamic tikkun olam, a project for healing the world that moves beyond mere metaphor. It has motivated incredible projects such as localized tree planting and inhabits a perfect space for protest actions, just like “liberation seders” did in decades past. But another memory inhabits it simultaneously, what else these trees have symbolized. The same tree, in different land in different contexts, holding two different social roles, dispossession packaged as salvation.

Subscribe to the newsletter

The JNF calls Tu B'Shevat the “original Earth day,” asking Jews to plant trees across the globe, though their program directs those roots towards the Land of Israel. Starting in the 1970s, partially because of the creation of the modern environmental movement simultaneous to the growth of the Jewish New Left, many began exploring the natively Jewish relationship between adam-adamah, humans and the Earth. A common argument of the time was that Judaism and Christianity were both religions that pulled God out of the Earth and made them separate from their creation. This desacralized the Earth, so the claim goes, destroying animist consciousness and creating the distance necessary for an entire civilization based on emotionless environmental exploitation. Whether or not this is inherently true about Christianity is debatable, but it is markedly untrue about Judaism. As people like Ami Weintraub have argued, there is a type of animism present in the Jewish mystical understanding of God's immanence flowing through all things. It takes little Jewish knowledge to realize that Judaism is a religion centered in the flora and fauna, from the agriculturally focused holidays like Sukkot to the Rosh Chodesh celebrations of the moon cycles to more recent developments like the Earth-Based Judaism of the Jewish Renewal movement.

This connectivity between Judaism and the natural world also tracks with the image of rootedness underlying Tu B’Shevat. Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the final Lubavitcher rebbe, suggested that hashem had, as Desher Magazine recently argued, "'sowed' the Jews in galut Mitzrayim so that there could be a greater revelation of His glory down on Earth. Just as when one plants, a few seeds can yield an abundance of crop, so too, Hashem sent the Jews to Egypt to bring about an increase in Godliness." Other diasporic mystics made similar observations, that God’s light detonated during the primal shattering, spreading shards of Jewishness across the world and, simultaneously, embedding that Jewish light amongst the nations. Through the grand explosion outlined in the Lurianic kabbalah, G-d’s light was dispersed through tall peoples, planting pockets of holiness of their own that might evolve into redemption. “Just as the seed must burst in order to sprout and blossom,” writes Gershom Scholem in Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, “so too the first bowls had to be shattered in order that the divine light, the cosmic seed so to speak, might fulfill its function.” Perhaps we have been planting seeds for centuries, waiting for new trees to grow.

This was reflected in the Reform Movement’s concept of Rabbinic Stewardship, which guided a great deal of that early Jewish environmental activism. The Tu B’Shevat seder has become an environmental consciousness raising exercise, which is why it is common to hold it as a vegetarian or vegan meal, projecting environmentally coded behaviors onto the narrative event itself. But simultaneously, the JNF has centered itself in Jewish environmental discourse, suggesting its project of land acquisition and transformation represents the unity of Jewish Earth-based consciousness. There is an unacknowledged dystopian element to this: if the JNF is both a positive affirmation of Jewishness and an effective tool for the repair of the biosphere, then the cost it comes with, the mass dispossession of Palestinians, must likewise be a price we must bear. The idea that the environment holds a tragic dimension, that it is natural to oppress certain people in the name of ecological preservation, is an impulse that has motivated the entire history of the environmental movement.

Reactionary Environmentalism

Modern environmentalism as a social movement emerged from the panicked reactions to modernity, the loss of traditional folkways that people later romanticized (in the Romantic Period, no less) as what had rooted them to the Earth. There was a dialectic to this process, the increased modernization and technological advance created a yearning for some type of mythic pre-modern past. It would be wrong to suggest these desires were only manifested in reactionary political ideas, but it did bring us the revival of Germanic paganism (which a racial bent) and the volkisch movements that claimed both ethnic consciousness and biocentrism, implicitly suggesting one was tied to the other. Like much on the far-right, they assert that a true environmental movement, one that centers the true nature of the Earth, is one that propagates hierarchies, domination, and a ruthless “natural law.” If this is the state of nature, then they want our social and political systems to reflect that as well, subsequently arguing that their vision of authoritarian racist nationalism is codified in the rhythms of the land.

America’s early conservation movement was absolutely indistinguishable from what we know today as proto-white nationalism, the effort to fight for the “white race” as a political category. Its most prominent proponent was Madison Grant (who was essential to establishing the National Parks), who believed we had to protect our dwindling resources, our flora and fauna. But top of the list was the white race, whose he believed had its hegemony threatened by a wave of sub-human non-whites ready to completely overwhelm all of their pure white faces. They would consume us, if we let them, so why not conserve our most precious resource: ourselves. The exact same line would be echoed from the stage of the white nationalist conference American Renaissance nearly a century later, as Jared Taylor, their pseudoscientific leader, used liberal-friendly talking points to stoke racist panic. Grant’s book The Passing of the Great Race became a runaway best-seller, and along with Lothrop Stoddard’s The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy, establishing an early version of the “Great Replacement Theory,” the notion that whites were being systematically replaced by non-whites, a more animal-like species who will rip apart not only our civilization, but our planet as well.

America changed in the decades that followed, particularly after the end of World War II and the successes of the Civil Rights Movement, and after the passage of the 1965 Civil Rights Act, which liberalized many of the quotas that had kept out immigrants of color. Part of the pushback to these immigration reforms came out of a piece of the environmental movement. While we may remember books like Silent Spring as the center of this renewed environmental consciousness, just as important were volumes like Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb and Garret Hardin’s essay “The Tragedy of the Commons,” each containing a barely coded disdain for the non-white world. Humans (at least some humans) were a virus threatening the entire ecosphere, and these ideas filtered into groups like the Sierra Club. While the environmental movement won groundbreaking legislation in this period like the Clean Water Act of 1972, the Endangered Species Act of 1973, and the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970, anti-immigrant nativism had also been a trenchant part of that consciousness.

This brought figures like Eihlic into contact with a young John Tanton, an environmentalist concerned with the threat of overpopulation who would, in 1975, become the President of a group Zero Population Growth, putting them into further contact with white supremacists. Tanton’s later history has pushed many in the modern green movement to label him a cynical entryist, but he was not disingenuous: he had been reacting to the crisis of consumer waste in the 1960s and helped, with family money, to found groups like the Bear River Commission in 1966 to help clean up the Bear River in Petoskey, Michigan, where he lived out his life. Along with his wife Mary Lou, who herself had been active in the fight for abortion access (our reader could likely guess why), he built what became known as the “Tanton Network,” a leading confederation of anti-immigrant groups that today have become central to the right’s fight for border restrictions: NumbersUSA, the Center for Immigration Studies, and, most famously, the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR). This is where the environmental movement emerged from, a panicked reaction to modernity and the overlap between fears of environmental degradation and the perceived threat non-white immigrants posed to white supremacy.

The fragmentation continued into the 1980s, as movements like Earth First! pushed into the radical left, though were still attached to far-right anti-immigrant activists like Dave Foreman. While the contemporary environmental movement has mostly eradicated these influences, there are still defectors, like when former Earth Liberation Front prisoners become esoteric fascists or when direct-action activists decide to create an authoritarian, transphobic network called Deep Green Resistance.

Subscribe to the newsletter

White nationalists themselves cultivated their own internal eco-consciousness as well. The reality of a growing ecofascism became a part of the public conversation in 2019 when mass shooters in Christchurch and El Paso explicitly referred to ecofascist ideas in their manifestos, claiming to be in both a struggle for the white race and the future of the planet. "This is the logical conclusion of this white genocide, Great Replacement conspiracy theory slash this fantasy of existential doom that many on the far-right...have been dabbling in for decades now,” journalist Brendan O’Connor, who writes about far-right and “border fascism,” told me, noting that it is this fear of “being swamped” that feeds their terrifying acts. Figures like Pentti Linkola, a Finnish ecologist who argues for mass genocide as the only solution to sustainability saw a resurgence, as is terror factions inspired by Theodore Kaczynski.

This is not the story of the mainstream environmental movement today, nor should this be used to tarnish groups like Extinction Rebellion who get slandered with terms like “ecofascism” by a political right who disingenuously wants to tarnish their reputation. But it is also the environmental movement’s parallel history, one that has found sincere inspiration in many of the central talking points of ecological activism: that the world is eroding and only dramatic action can respond. The romanticism associated with the far-right’s ecological obsession bears some comparison to some of the obsessions with land offered by some early Zionists, who believed that placing Jewish blood in some soil would redeem them, and that only the Jewish control of captured land would ensure its prosperity.

Who’s Environmentalism?

What many “biocentrist” arguments lack is a grounded way of connecting environmental struggle with the flesh and blood humans interacting with that ecosystem. Biocentrism seeks to approach the environment on its own terms, but that says little about how this type of movement interacts with other, overlapping forms of oppression. Instead, an intersectional approach can center human experiences as a way of anchoring us to what can feel like overwhelming and abstract questions about the Earth’s future. When I was working with Genesee Valley Earth First!, eventually joining the Marcellus Shale Earth First! (later renamed the Marcellus Shale Action Network) to fight fracking across the lands of New York State and Pennsylvania that sat on the shale. Part of what drew us to fracking was that it recentered affected communities, usually poor, working class communities, in what ended up as a struggle over water integrity. Our approach was no longer about restoring some mythic “state of nature,” it was about protecting the environment as much as it affected living humans who depended on it. The issues became intertwined: gender, racial, and economic justice were becoming indistinguishable from the environmental fight, something that helped to guarantee its success in making measurable gains.

The question of immediate demands and long-term political implications are always a conflict in social movements. Around recent issues like the 2018 U.S. bombing of Syria or the recent Russian invasion of Ukraine, a certain segment of the left were stalwarts in support of the reactionary regimes of people like Bashar Al-Assad or Vladimir Putin simply based on the resistance shown to U.S. imperialism. By disrupting the dominant actor on the international stage and pushing for multipolarity, they suggest, we have struck an essential blow against the center of so much pain and misery. But this approach simply borrows from Peter to pay Paul: we don’t oppose U.S. imperialism because the U.S. is cosmically evil, we do it because it conflicts with foundational principles of equality, liberation, and, ostensibly, freedom for all peoples. If the primary opponents in this fight are likewise reactionary militarists, waging their own war for imperialist hegemony, then how are they our “allies” in building a new world?

This ideological unevenness is not just a bug of social movements, it’s a feature of the broad coalitions we often need to make any gains. Fundamental conflicts can become invisible when overshadowed by immediate goals, or simply by capturing movement rhetoric for illiberal ends. By stealing away the language of Jewish environmentalism, the JNF does offer a vision of a type of world-healing, the mechanism of which is the capture of land from Palestinian families. Tu B’Shevat then becomes its own type of contested space, a battle over what the implications of a specifically Jewish environmentalism could be. By suggesting that environmental healing comes only at the cost of Palestinian dispossession (which is the implications of its strategy), you create a sort of tactical anti-liberation: the suggestion that we can save the world by placing the cost on another people. In looking at the midrashic debates over the holiday’s significance it is hard to ignore the overarching metaphor of seed planting: Torah (Wisdom) plants the seeds so a whole world can branch and blossom. Which kind of world will it be? What kind of “saved” Earth will result?

There is nothing inherently liberating about the environmental movement, unless that movement sees saving the Earth as just one part of eradicating suffering and oppression for all. That is why Jewish radicals have turned their attention to the “forest defenders” near Atlanta, who have been spending years now blocking the destruction of a forest region to build a police complex colloquially known as “cop city” as well as an entirely unnecessary film studio. The radical Jewish Fayer Collective put out a statement connecting their acts of resistance to the Shmita year: the seventh year in a planting cycle where the land is allowed to lie fallow, owing to the laws outlined in Leviticus. Shabbat is such an all encompassing cosmic force that even the land engages in rest one year out of seven, but for the resisters, they had to break the laws of rest if they were ever to protect the future of the land’s Shmita. “For a millenia we’ve forsaken the Shmita, and now we owe a massive debt: a debt of rest, of unpruned vines, of unfreed slaves, of the destruction of debt itself,” they write in their manifesto, noting that the Earth demands, unequivocally, that it be allowed to restore balance by having periods where human cease to plow its fields or trim its branches. “The Kabbalists say that this world was made through tzimtzum: the contraction of God’s infinite light, a divine act of negation to make creation possible. Today the voice of God speaks through the ‘crrreeeaaaaak…Boom!’ of an exploded gas tank. Shmita means attack; Shmita means total destroy.” They acknowledge that there is an entire Jewish NGO infrastructure asking that people participate in Shmita as an environmental exercise: hit the donation button, go green, even plant a tree. But there is an explicit contradiction in these civic organizations: they offer the claim of environmental liberation, but instead invite you to participate in the further dispossession of those facing the consequences of oppression most acutely.

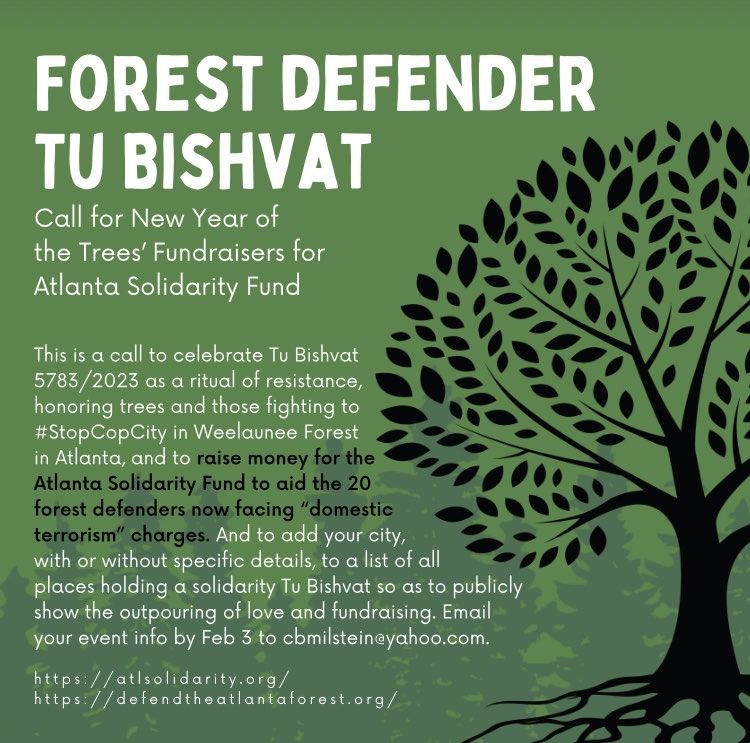

For 2023’s Tu B'Shevat, the pressing crisis affecting the Atlanta Forest, and the cruel violence directed at forest defender Manuel Esteban Paez Terán, beter known as Tortuguita, who was killed on January 18th, has led Jewish radicals to align the holiday with the kind of environmental struggle that is unified under a more inclusive vision of what liberation could look like. Calls by people like Jewish anarchist Cindy Milstein brought people into fundraising projects to support the forest defenders, like rallies and calls for tzedakah to be directed their way. Similar to the support of abortion funds in the wake of the Roe ruling in 2022, we can harness the Jewish community’s commitment to participate in tikkun olam on these holidays to support a more liberatory vision for an environmental movement. While the JNF uses the language of the environmental movement to push out an entire people from their land, the Atlanta Forest Defenders are honoring the indigenous holders of the forest they are standing on, facing criminalization and charges of terrorism. If we are to live up to the promise of Tu B’Shevat, it's in solidarity with those who have the capacity to let the seeds of a new world grow.

A Tu B’Shevat that puts un in concert with where Earth defense actually is, not simply to reproduce a culturally-homogenous version of planetary healing based solely on the acquisition of sovereign land, but one that allows a distinctly Jewish voice to be part of the larger web of solidarity that successful movements are drawn on. This is part of where the return of the Jewish radical left is finding its efficacy and ability to reproduce itself: by offering a uniquely Jewish approach to pressing crises.

For 2023’s Tu B’Shevat, Jewish radicals from around the U.S. (and, around the world) are holding events, fundraisers, and celebrations that align with the escalating fight to defend the Atlanta forests. Here is a partial list of different events and fundraisers you can tie into as an alternative to the large Jewish civic organizations who are asking for feckless donations on the one side, or whose vision of ecological repair is centered in the JNF’s ability to capture, and transform, land on the other.

- Tu B'Shevat Forest Defense Solidarity Seder and Potluck - Worcester, MA (2/5 - 6:00pm EST)

- Tu B'Shevat Herbal Care Package Raffle to Raise Money for Forest Defenders

- Liberation at the Pace of Trees: Fundraising Ritual (2/5 - 6:00pm, Bushwick, Brooklyn)

- Stop Cop City: Tu B'Shevat Raffle by Jewish Zine Archive

- Jewish Plant Magic Raffle to Benefit Atlanta Forest Defenders

- Direct Tu B’Shevat Donations to Atlanta Solidarity Fund

- Ceramics Raffle for Tu B'shevat to Support the Atlanta Solidarity Fund

- Tu B'Shevat Ceramics and Candle Raffle for Atlanta Solidarity Fund

Click here to learn more about Defend Atlanta Forests and all the ways you can support them. You can also follow them on Twitter, and prepare for the upcoming week of action starting February 19th and going until the 26th.